�

�

Bill Thumel and his NOJ 391 replica at a photo shoot for the 2005 Australia / U.S.A. Healey Challenge

�

NOJ 391 Replica : Bill Thumel's Austin Healey 100

�How Tom Kovacs recreated one of the most historic and famous of the Healey

�

works racecars, with help from Geoff Healey and Roger Menadue.

�

�

Early Austin Healey History

��

When Donald Healey and his small team at the Donald Healey Motor Company developed �

the Healey 100 sports car, they built it around mechanical components from British Motor �

Company's "Austin A90 Atlantic". The model name "100" was selected because �

their goal was to produce a modern, economical sports car that would reach 100mph. �

They built one prototype and took it to the 1952 London Motor Show where it was very �

well received. Before the show was over BMC Managing Director Leonard Lord agreed to �

enter a cooperative arrangement with Healey to build and distribute "Austin Healey" �

sports cars. Working together they even managed to get an "Austin Healey" badge cast �

by a London jeweler, and they installed it on the prototype before the end of the show.�

�

By summer 1953, BMC would be building the new Austin Healey 100 model in its Longbridge �

factory, alongside A90 sedans. However, before serial production started there would be �

a need for more prototypes and for show cars. DHMC placed an order for twenty all-aluminum �

prototype car bodies.1 Aluminum was Healey's preferred body material because �

it's about one third the weight of steel, assuming the same thickness. The downside �

of aluminum bodies compared to steel was that they were more expensive, more easily �

damaged, and trickier to repair. Like all the "big Healeys" that followed, the 100 was �

a body-on-frame design. For strength and durability, frames were made of steel.�

�

The first four of the new prototype bodies were built-up into show cars, three of which�

were dispatched to U.S.A. in early 1953. The fourth was dispatched to Switzerland�

for the Geneva Motor Show. Ultimately, nineteen of the twenty prototype bodies became �

cars and many of them still exist in some form. According to one account, when the show �

cars arrived in U.S.A. dinged-up, a decision was made to replace most of the aluminum body �

with steel panels for serial production. �

Decisions of that magnitude are hard to implement quickly, but by sometime in July 1953�

the supply of less than 300 all-aluminum bodies was used up. Press tooling was modified to �

accomodate the different spring-back characteristics of steel. Door skins and fenders,�

front and rear, were switched to steel relatively quickly whereas the hood and trunk lid �

were switched from aluminum to steel in May 1954 and June 1955 respectively. �

Healey's Special Test Cars

��

Donald Healey had long enjoyed and succeeded in racing, both as a driver and as an �

engineer. He now recognized that racing success would build credibility for his new �

joint venture with Austin. As the development team finished designing the base-model �

"100", Donald Healey directed their attention to building four "works" racecars. �

All-aluminum prototype bodies (number "5", "6", "7" and "8" of the original twenty) �

were used for these "Special Test Cars". As these cars were built, they were given �

serial numbers "SPL224B", "SPL225B", "SPL226B", and "SPL227B" respectively. Since �

the first three Special Test Cars would occasionally be driven on public roads, �

they were registered and licensed; they were assigned license numbers "NOJ 391", �

"NOJ 392",and "NOJ 393" respectively. SPL227B was specifically intended for speed �

trials, so it was never licensed.�

�

As is virtually inevitable in any active racing program, the Special Test Cars were �

continually improved. They were also modified to comply with rules and competitive�

requirements of different races. Ideas were tested on these cars that would later be �

used in production. In fact, a special edition model called "100S" was based closely�

on the Special Test Cars. The story is that Briggs Cunningham saw the cars racing at �

LeMans in 1953 and asked Donald Healey to build him a car just like them; this �

request inspired the whole 100S program. �

�

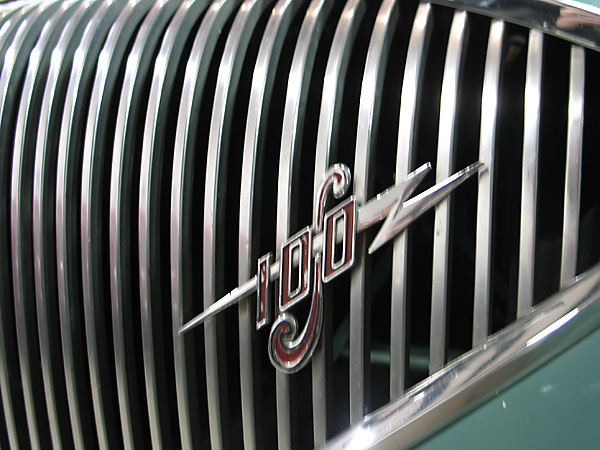

Ultimately the 100S model would weigh about two hundred pounds less than the base model, �

due in part to aluminum fenders and bulkheads. An oval grille replaced the larger fan-shaped �

grille of the 100, purportedly to improve aerodynamics. Bumpers were omitted. A �

better-breathing aluminum cylinder head by Harry Westlake and a higher compression ratio �

helped to boost engine performance: Austin Healey rated the 100S engine 132bhp at 4700rpm �

versus 90bhp at 4000rpm. All wheel Dunlop disc brakes compared favorably to the drum brakes �

on the base-model. The 100S was specifically targeted toward "gentlemen racers". �

About 50 100S cars were built between October 1954 and September 1956, and about 37 �

are known to have survived. Additionally, at least one and possibly two of the three �

original Special Test Cars were rebuilt and rebadged "100S". �

�

�

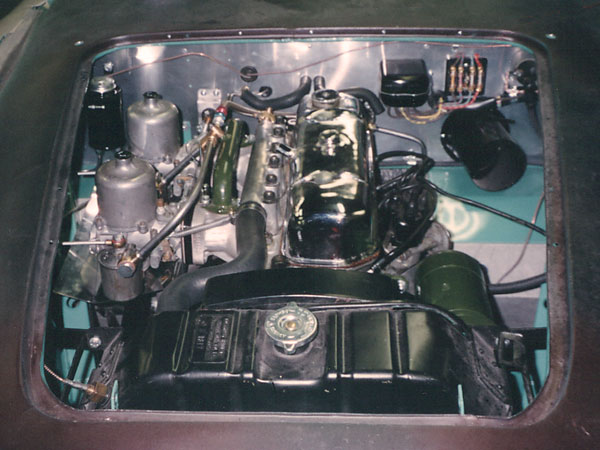

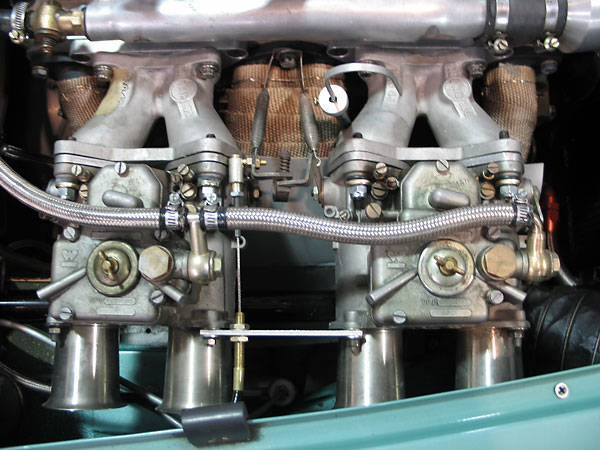

Except for Weber carburetors, which have temporarily been installed instead of S.U.'s, this photo

�

gives a pretty accurate idea what NOJ 391's engine compartment looked like at Sebring in 1954.

�

� What happened to the original Special Test Cars? Although there are areas of cloudiness and � contention, we can summarize their fate as follows. After several years of racing, the Healey � family decided to retire NOJ 391 from racing. It was returned to Warwick to be rebuilt as a 100S. � They reportedly intended to present it to Ed Bussey, proprietor of "Ship and Shore Motors" of � Florida who had helped them achieve success with it in the Sebring endurance race. (NOJ 391 had � scored a remarkable third-place overall, and finished first in its class.) Ed Bussey's rebuilt� car continued to race for many years. NOJ 392 had a relatively short racing career, before it � was retired. It was given to Roger Menadue who enjoyed it as a road car for over ten years, � but he ultimately sold it. It's been carefully restored and is well maintained to this day. � NOJ 393 participated in the 1953 24 Hours of LeMans race. After being rebuilt and rebadged as � a "100S", NOJ 393 was involved in the famously horrible crash at the 1955 LeMans race. It was � rebuilt yet again, and it still exists in England. On December 1, 2011 NOJ393 sold for £843,000� at auction - probably the highest price ever paid for any Austin Healey. SPL227B was used� for speed trials at Bonneville in 1953, 54 and 56, then rebuilt and raced at Sebring in 1957,� before being destroyed in 1962. �

��

Enjoying this article? www.BritishRaceCar.com is partially funded through generous support from readers like you!

�

To contribute to our operating budget, please click here and follow the instructions.

�

(Suggested contribution is twenty bucks per year. Feel free to give more!)�

An Unlikely Series of Events

�� The most heavily raced of the four Special Test Cars was arguably the first one, number NOJ 391.� In addition to its remarkable best-in-class and third-place-overall finish at the 1954 � Sebring (12 hour) race, NOJ 391 also participated in the following races, rallies and hillclimbs: �

�| year | race / event | result | year | race / event | result | ||

| 1953 | Mille Miglia (1000 miles) | DNF (clutch) | 1953 | LeMans (24 hours) | DNS (2) | ||

| 1953 | Goodwood (9 hours) | 10th overall | 1954 | Mille Miglia (1000 miles) | 23rd overall | ||

| 1954 | Prescott Hillclimb | 1954 | Shelsley Walsh Hillclimb | ||||

| 1954 | Alpine Rally (~2600 miles) | 25th overall | 1954 | Tour de France (~2500 miles) | DNF |

�

According to some reports, NOJ 391 was also taken along on DHMC's 1954 pilgrimage to �

the Bonneville salt flats, where it achieved a record speed of 142.64mph over a flying mile.�

Close inspection of photographs from that trip suggest that in fact the only part of �

NOJ 391 that actually traveled to Bonneville was the license plate. You don't need a �

license plate to race at Bonneville, but the Healeys weren't above a little creative �

marketing! �

�

NOJ 391 was stripped down after the 1954 season, to be rebuilt as a "100S" and to be given �

away to Ed Bussey who was a friend of the Healey family. Much of the original bodywork �

was removed and replaced, including the grille. The distinctive original "fan-shaped"�

grille was replaced with the oval grille of the new 100S model, which obviously �

meant replacing the surrounding metal too. The aluminum body was painted bright red, �

and a black interior was installed. The reborn car was almost ready to ship to its �

new owner... but at the last moment Donald Healey realized a shortage of new 100S race�

cars to replace the Special Test cars for the 1955 season. This "new" 100S would �

be borrowed for the Mille Miglia endurance race (finishing third in class and eleventh�

overall), and then again for Daytona Beach speed trials and for the Sebring endurance race �

(finishing 6th), before it was finally handed over to its new owner.�

�

Ed Bussey was himself an enthusiastic racer, and he drove his ex-works racecar in �

various SCCA races. After Bussey sold the 100S in 1959, it passed through the �

the hands of a couple more owners. Somehow, apparently, its full racing history wasn't �

communicated to SCCA racer Fred Hunter when he bought it in 1966. After Mr. Hunter �

stopped racing the car, he put it into long term storage. He decided to get quotes �

for its professional restoration in 1988. While preparing to quote the job, Healey �

specialist Tom Kovacs realized this car wasn't quite the 100S its owner thought it was! �

He contacted Geoff Healey and Roger Menadue. Very interested, they inspected it and �

excitedly confirmed its identity. �

�

�

The all-aluminum doors of the Ed Bussey / Fred Hunter 100S were painted the original Healey

�

works racing team's color, "Ice Green Metallic," before they were repainted red.

�

� But what to do? Fred Hunter's car had apparently been very famous and successful in two � different incarnations. Ultimately, Fred Hunter decided that his 100S would be restored � to 1955 Mille Miglia specification and appearance. Inspired by that car and by the history � he learned from Geoff Healey and Roger Menadue, Tom Kovacs decided to create a replica� of NOJ 391 as it appeared at Sebring in 1954. Healey and Menadue were happy to help. � The resulting replica is the car we show here. �

��

�

Healey / Type: BN151958

�

Chassis No: (Roger Menadue's signature)

�

Engine No: (Geoff Healey's signature)

�

Donald Healey Motor Co. Ltd. / Warwick / England

�

Note: Roger Menadue was Healey's longest serving employee and was also the engineer �

who headed their experimental department when the 100S was developed. He was born on �

August 23, 1912, and he died on March 12, 2003, aged 90. Geoff Healey was, of course, �

Donald Healey's son. (December 14th 1922 - April 29th 1994)

�

Creating the NOJ391 Replica

��

The stars must have been in perfect alignment when Tom Kovacs decided to build a �

replica of NOJ 391. Having the enthusiastic support of Geoff Healey and Roger Menadue�

certainly didn't hurt, but indeed the project captured the imagination of many Healey �

enthusiasts. Offers of rare competition parts began to come in from far-flung and �

unexpected places.�

�

Also, one of Geoff Healey's earliest suggestions proved tremendously helpful.�

Geoff asked: "Why not imagine how NOJ 391 would have been improved if our �

Warwick shop had continued working with it through the 1960's? We would have kept �

the car lightweight and simple, but we would have upgraded it too. We would have used �

parts from later model Healeys where it made sense to do so!" There are two key �

implications to this suggestion: the search for "correct" parts didn't need to be �

so exactingly difficult and the car would ultimately be both faster and more robust. �

�

BN151958 was an ordinary 1954 Austin Healey 100. It came with a clear title, and�

since it was a 1954 model, it also came with an aluminum bonnet and boot lid (in �

addition to aluminum front and rear shrouds, of course.) It was a good starting�

point for the project. Ultimately though, quite a lot of BN151958 wasn't used. �

For example, reproduction aluminum fenders (front and rear) are still available �

from an English supplier, so a set was ordered. A replacement superstructure was�

special ordered from a supplier in Australia. When the superstructure arrived, �

carefully following directions from Roger Menadue, Tom Kovacs punched and swaged �

lightening/stiffening holes throughout. The steel firewall was deliberately�

left in place, clad with a new aluminum cover, due to safety considerations. �

�

�

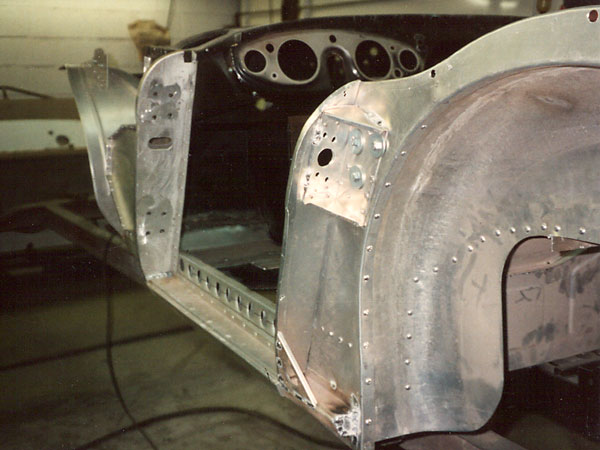

New alloy superstructure. This photo shows lightening/stiffening holes being added along the door sill.

�

Note that BN151958's firewall (and original left-hand-drive dashboard) was in place at this stage.

�

�

Tom stripped off BN151958's steel door skins and fabricated his own aluminum replacements.

�

�

Test fitting the grille, and refining alignment of the new aluminum fenders.

�

� The standard BN1 engine was replaced by a rare, original 100S engine (purchased used). � A couple things to note about this engine: the compression ratio on these engines was � low by racing standards, at about 9.1:1, so that it could run on poor quality "pump gas". � Since the distributor drive has been moved to the opposite side of the � engine block compared to a regular BN1 engine, the 100S model's Mallory YCM distributor � had to spin clockwise instead of counterclockwise. The 100S cylinder head didn't come with a � provision for a thermostat, so Tom custom made one. It was used in conjunction with � the stock BN1 radiator. A late-model oil cooler was installed in lieu of the inefficient � "hippo" style oil cooler as originally used on NOJ 391, and for easy maintenance a � spin-on oil filter was installed on a remote-mount base. �

��

�

Here, an authentic Austin Healey 100S engine has been installed in BN151958. (Note: fenders still in primer.)

�

The 100S model featured 1.75" S.U. carburetors. This car and the works racers would use the 2.0" version.

�

�

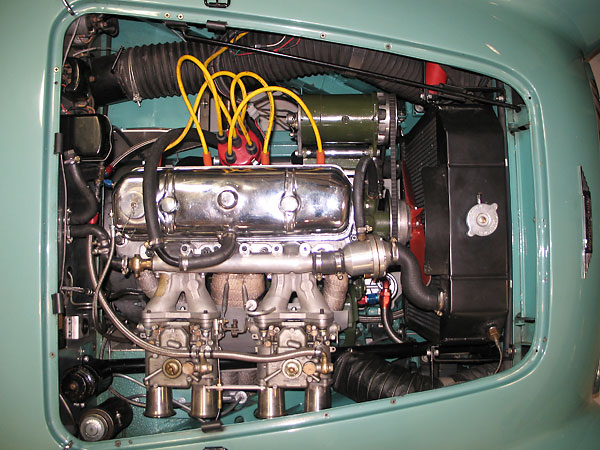

Since original 100S engines are quite rare, Bill Thumel has subsequently removed that engine and set it aside

�

for safe keeping. So, the engine shown in this newer photograph is actually a race-prepared replica built from

�

a modified BN1 engine block and a reproduction Westlake 100S cylinder head. Its compression ratio has

�

been raised to about 12:1. Weber DCOE carbs and a Mallory Unilite distributor have been installed.

�

�

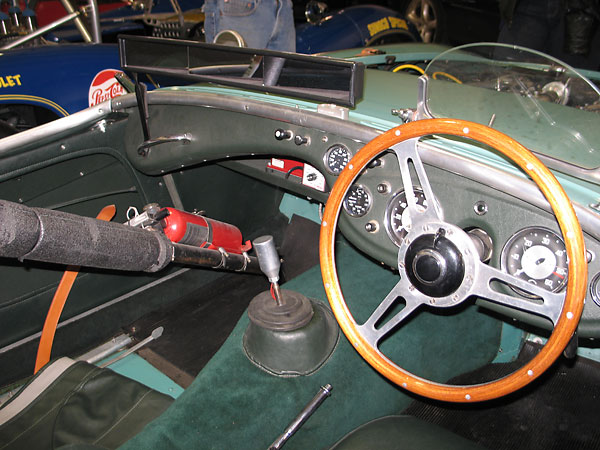

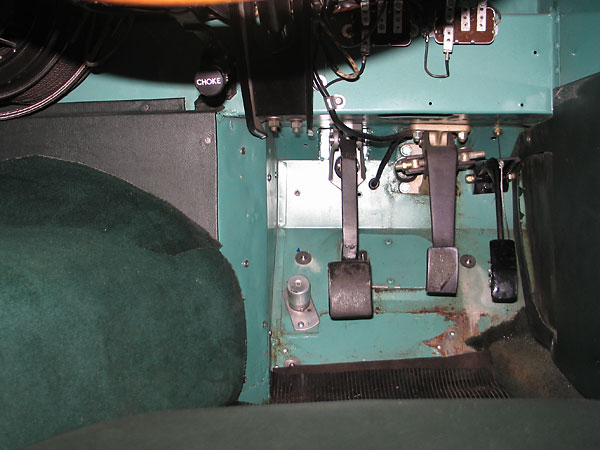

A decision was made early-on to couple the engine to a 1961 BJ7 ("3616") gearbox. This is �

much stronger box than the regular four cylinder (BN1 and BN2) cars had, and although the �

gear ratios aren't optimal, it's the most suitable of the "six cylinder" gear boxes. �

At the suggestion of Geoff Healey a center-mounted shifter was installed, even though �

100S cars were built with offset shifters. Geoff insisted that factory team never raced �

with an offset shifter.�

�

A 28.6 percent overdrive unit was used (like the four cylinder cars came with �

from mid-1953, instead of the later 21.7 percent overdrive). The earlier overdrive �

suits the small engine better. Overdrive is only useful in top gear: in third gear, �

switching into overdrive provides the same effect as simply shifting into fourth. �

There are actually two electric switches wired in parallel for engaging overdrive: �

one on the shifter and the other one on the dashboard just to the left of the steering �

wheel.�

�

Incidentally, all the wiring has been specially built to replicate Lucas �

competition wiring, and it features a four-fuse fuse block and cloth insulation.�

�

�

1963 "banjo" type axle. Note also the N.O.S. Armstrong "blue" shock absorber in the foreground.

�

� Tom decided to install a later model ("six cylinder") rear axle for several reasons. Although � it's relatively heavy, it's also certainly more robust than the earlier axle. It features � hypoid gears instead of spiral-bevel gears, and larger outboard bearings, plus five stud � hubs instead of four stud. Tom also decided to install a Quaife gear-operated limited slip � differential. Although not period correct, the Quaife differential is torque biasing. � (A limited selection of clutch-type limited slip differentials would have been available � in the late sixties, but they were never installed on production Healeys.) �

��

�

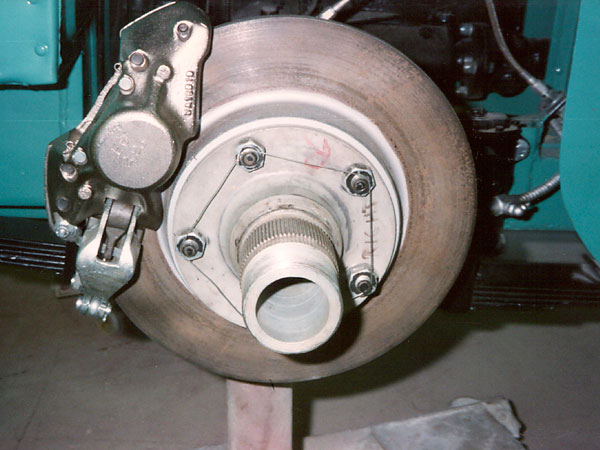

Girling rear brakes are a whole lot more practical than authentic Dunlop disc brakes would've been!

�

� Besides being heavier duty, brake compatibility pointed Tom toward the later model axle. � Early axles had four-stud axle shafts, whereas later axles have five stud shafts. � Four cylinder production Healeys like BN151958 came with drum brakes all the way around. � Tom considered upgrading to Jaguar-spec Dunlop disc brakes, as were fitted to NOJ 391 and the � other Special Test Cars in 1953. However, he was offered a full set of Girling disc brakes � from a works 1963 Sebring racecar, and he couldn't turn that down! The Girling brakes � mount to five stud axle shafts. �

��

�

During his summer vacation, Roger Menadue came to visit and check progress on the NOJ 391 project.

�

As shown here, he just couldn't resist the opportunity to dig-in and turn a few wrenches!

�

� Geoff Healey endorsed this decision because the Jaguar/Dunlop brakes were a big compromise � from the very beginning. Those early "banana" brakes are physically large, which obliged � the factory team to race on 16" wheels. With the tires that were available for them, the � difference in ride height was enough to compromise handling. The difference in unsprung � weight and polar moment (flywheel effect) was significant too - and the larger wheel/tire � combination obliged the team to cut bigger wheel openings in their beautiful fenders. A � less obvious disadvantage of the Jaguar/Dunlop brakes was that they were hydraulically � servo-assisted - not pneumatically servo-assisted like modern brake systems. They required � a transmission-driven servo pump and a sizable fluid reservoir. Since the Austin transmissions � didn't have a pump, Aston Martin transmissions were used. The pumps cost horsepower at � speed! At low speeds and when reversing, brake effectiveness was severely compromised. � Finally, on the original Special Test Cars there was no convenient place to mount the � hydraulic pump, and the brake fluid reservoir was cut into the firewall. Understandably, � as soon as they could, Healey stopped using this early version of the Dunlop disc brake system.�

��

�

Through the 1954 Sebring race NOJ 391 raced on 16" spoke wheels by necessity, not preference. Authentic Minilite

�

15" magnesium wheels were substituted here, on the strong recommendation of Geoff Healey.

�

�

At the rear, BN1's knee-action Armstrong shock absorbers were replaced with heavier �

duty "new old stock" 100S shocks. These shocks are quite a bit larger, similar to �

DAS10 shocks on a BJ8, but they're hard to come by because they have special forged arms �

unique to the 100S. (Isn't it remarkable that tooling for special forgings was ordered �

for a production run of only fifty cars?) �

�

Like the works team, Tom left the front shock absorbers alone except for upgrading to �

a stiffer valve. ("Top-hat" dual-acting valves that provide different dampening during �

bump and rebound weren't used until very much later.) �

�

BritishRaceCar.com appreciates the generous help Tom and Kaye Kovacs have provided with this article.

�

Their company, Fourintune Garage Inc. of Cedarburg WI is nationally famous for its expertise with Austin Healeys.

�

Visit the Fourintune website for additional information on the reconstruction of NOJ 391.

�

�

Quite a lot of more subtle changes were made to the chassis too:�

�

The left-hand-drive BN1's steering box was replaced and upgraded to a right-hand-drive �

1961 "Cam Gears" (15:1) steering box, which provides lighter steering.�

�

Although a 100S front anti-sway bar was found for the car, at the instruction of �

Geoff Healey, Tom kept looking until he found a works-style anti-sway bar. The key �

advantage of the works-style bar is rose-jointed connections. If a pin joint breaks �

while racing, the driver could lose control of the car!�

�

No rear anti-sway bar was installed, but the Panhard rod was upgraded slightly: its ends �

were changed from rubber bushes to rose joints for more precise axle location. �

�

�

Understatement: through the 1950's it was customary to leave carpet and upholstery in place.

�

�

Throughout the time Tom owned and enjoyed the car, he was determined to keep it a �

dual-purpose car: one that could be enjoyed on a pleasant Sunday drive or on the �

the racetrack. To this end, a couple small concessions were made to comfort. For example, �

the heater was left in place, and the battery wasn't located where the works team certainly �

would have had it. Back in the day, the battery would have been located in the �

passenger-side footbox, but instead its in the production location (behind the seats.)�

�

Although the car is shown below with authentic Aeroscreen windshield, a regular Austin Healey 100�

windscreen is also provided and can be swapped onto the car. A convertible top is ready to �

be installed too. The car is shown below with a single Jaguar E-type (pre-1964) seat because �

it's stiffer and more supportive than a Healey seat, but Tom procured a matching pair of Austin �

Healey 100S seats (with distinctive slotted vents through the bolsters) that can be swapped in. �

Back in 1954 you wouldn't have seen a roll hoop in NOJ 391, but it's required for any track �

day or vintage racing use today. The driver-side door has also been provided with a tubular �

strengthener to resist side intrusion in the event of an accident. Even with these concessions, �

the car is remarkably balanced. Overall weight distribution is about 49% (front) / 51% (rear).�

�

The car made its racing debut at Road America's 1993 Chicago Historic Races. �

Roger Menadue helped with final preparations and served as crew chief. �

Driven by Phillip Coombs, the car finished second in its very first race, �

followed by first place finishes in group 3D. Coomb's fastest lap over the �

4.048 mile circuit was 2:53.479.�

�

�

Bill Thumel and the Healey prototype entering action at Virginial International Raceway in 2005

�

� Bill Thumel reports: "As far as racing it, I ran it a V.I.R. in 2005 at the Gold Cup. � It handled great but it was a bit underpowered. Abacus then started building a replacement � engine using a 100-4 block and converting it to accept the S head. It then ran � fantastic, with tons of torque. After a few changes it has now become very reliable � with about 12 to 1 compression and about 160 HP at the wheels.� The car is very neutral and fun to drive."�

� � � �Features and Specifications

�| Engine: | �standard Healey 100 engine, modified to accept a "100S" cylinder head. �

12:1 compression ratio. Westlake-designed 100S cylinder head. Weber �

DCOE carburetors (x2) on Derrington manifolds. Mallory Unilite distributor. �

MSD capacitive discharge ignition system, and separate dial-adjustable rev-limiter. �

(Both are discretely mounted under the dashboard. The rev-limiter was �

set to 5000rpm when we viewed the car.) Accel SuperStock 8mm spark plug �

wires. | �

| Cooling: | �stock Healey 100, except for a modern oil cooler. | �

| Exhaust: | �custom fabricated, tubular 4-into-1 header with high-temp wrap. | �

| Transmission: | �1961 Austin Healey 3000 Mark 2 (series BJ7) four speed manual, with (28.6%) overdrive. | �

| Rear Axle: | �100-6 axle with 5-stud shafts, 3.54:1 hypoid gears and Quaife limited slip differential. | �

| Brakes: | �(master) Wilwood dual master cylinders, with an adjustable bias bar. � (front) Girling rotors and calipers. � (rear) Girling rotors and calipers. | �

| Wheels/Tires: | �authentic Minilite 15" magnesium wheels with knock-offs, and Hoosier Speedster P185/65R15 tires. | �

| Body: | �aluminum superstructure and body, with extensive lightening holes added.�

"Ice green metallic" paint (the authentic 1953-54 works racecar color.)�

Leather bonnet and boot lid straps. | �

| Electrical: | �12V generator and battery (positive ground). The generator is the smaller, lighter �

style used on the 100S and early Sprites. | �

| Interior: | �early (pre-1964) Jaguar E-type seat. (Cut, narrowed, and reupholstered to fit.) �

Derrington (replica) steering wheel. Roll hoop. | �

| Instruments: | �stock, except for a 100S 140mph speedometer, plus an AutoMeter Sport Comp �

0-100psi oil pressure gauge which is discretely mounted under the dashboard. | �

| Weight: | �just over 2000 pounds, including driver and a quarter tank of gasoline. �

| �

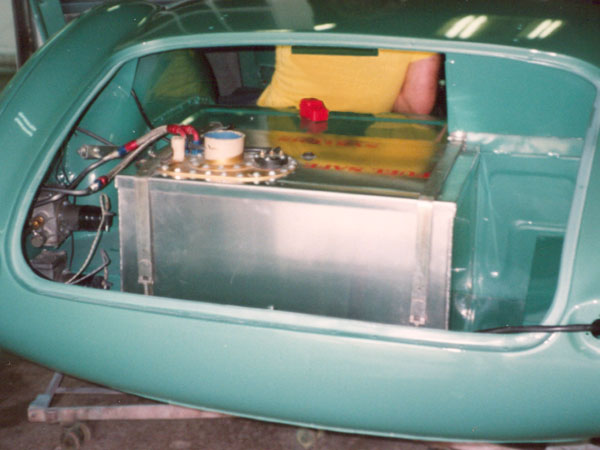

| Fuel System: | �25 gallon Fuel Safe fuel cell. | �

�

Engine Installation

��

�

Just to the right of the cylinder head, Tom Kovacs' custom machined remote thermostat housing.

�

�

S.U. carburetors were used for most of NOJ 391's career. By Sebring 1956, both works cars and

�

Ed Bussey (racer/owner of the re-bodied NOJ 391) were using twin DCOE Webers, like these.

�

The works team also began using tubular headers instead of cast iron manifolds at that time.

�

�

Harry Westlake designed his cylinder head to relocate both intake and exhaust to the opposite side

�

compared with the original Austin engine. This removed the obstacle of push rod tubes, and thus

�

facilitated eight bigger, better flowing ports - a change that's particularly beneficial at high RPM.

�

Stud and water port locations moved to accommodate this; so special engine blocks are needed too.

�

�

Here, a bare aluminum cover has been placed over the firewall to cover various holes.

�

�

Interior

��

�

This steering wheel is a copy of a "Derrington", with "fat" rim as preferred by several of the works drivers.

�

�

Aeroscreen perspex windshield (and modern "Wink" style mirror).

�

�

The MSD (p/n 8671) rev-limiter shown here is adjustable between 4600rpm and 6800rpm.

�

The AutoMeter Sport Comp oil pressure gauge reads between 0 and 100 psi.

�

�

A narrowed, pre-1964 Jaguar E-Type seat provides more support and stiffness than a Healey seat.

�

�

A pair of original, slotted "100S" seats were procured for the replica, for stylish off-track use.

�

�

Since the completed replica would be raced, a master cylinder upgrade was mandatory. A modern

�

Wilwood pedal assembly with dual master cylinders and an adjustable bias bar was installed, but

�

it's tucked away quite discretely.

�

�

Exterior

��

�

The color on this replica was color matched to original paint found on the door of Fred Hunter's car.

�

Roger Menadue explained that the light green color was selected instead of "British Racing Green"

�

because Donald Healey preferred it. Some sources report that Donald Healey felt darker colors made

�

small cars look heavy. Other sources claim he believed British Racing Green was unlucky.

�

�

The "100S" badge may be a little confusing on this BN1 grille, but NOJ 391 was the prototypical 100S.

�

�

The "Austin of England" badge was fitted on Austin Healeys until sometime in August 1954.

�

�

Raydyot mirrors are period correct, though works Healeys usually raced without side view mirrors.

�

�

The Special Test Cars were originally fitted with rubber-bladder aviation fuel tanks of ~24 gallon capacity.

�

For vintage racing, a modern Fuel Safe fuel cell of similarly huge capacity was installed.

�

�

Tom Kovacs installed a "LeMans style" fuel cap too. Its placement and the shape of the hole

�

and seal for it (in the boot lid) are based on sketches by Geoff Healey.

�

�

A true sports car in every sense. Race it on Sunday; drive it to work on Monday!

�

| Note: | |||||||

| (1) | �

The twenty original bodies were constructed at Jensen Motors in West Bromwich, just a few miles from�

the Warwick shop and the Longbridge works. They were made from "Birmabright", a specific alloy of �

aluminum with magnesium offered by The Birmetals Company of Birmingham England. Birmabright is an �

aircraft-grade aluminum, similar to "5251", and it's stronger than the alloys used later on production�

Healey bodies. � | ||||||

| (2) | �

NOJ 391 was smashed by a drunk driver right before the 1953 LeMans race. Since it would require extensive �

repair, components of the car including the NOJ 391 license plate were quickly removed and transferred to �

NOJ 392 for the actual race. This was expedient because NOJ 391 had already passed "scrutineering" and its �

engine had been "sealed" by race inspectors, whereas NOJ 392 hadn't even been registered to compete. The �

damaged car (i.e. the "original" NOJ 391) returned to England to be rebuilt. � This is where two schools of thought diverge. Some people believe the wrecked car was simply repaired � to continue participating at Goodwood (1953) plus the major races of 1954 as NOJ 391. (Indisputedly, the � wreck was repaired; what's disputed is which races it participated in.) However, there were at least � two "reserve cars" available to the Warwick shop in some stage of preparation, plus surplus components. � A second school of thought is that the Warwick shop may have assembled these into a new incarnation to � race as NOJ 391 in 1954. We're inclined to accept this second scenario based on statements made by Geoff Healey � and Roger Menadue upon careful inspection of Fred Hunter's car. During the inspection they discovered � distinctive hand-made parts that they associated with specific moments in the 1954 race season. Some � components from the 1953 LeMans wreck were identified too. � At the 1954 Tour de France race, the car entered as NOJ 391 suffered another wreck. Another rebuild followed.� (Obviously there were many opportunities for parts to move back and forth between cars.) � The 100S owned and raced by Ed Bussey and later owned and raced by Fred Hunter was clearly made from a� rebuilt "reserve car". Its frame was built after 1953 (as evidenced by flanged joints). The key issue � really boils down to two questions: (1) Did that reserve car race as NOJ 391 in 1954? (2) If it did, which � races did it compete in? (Particularly, was it the very same car that was so successful at Sebring?) � DHMC's record-keeping and registration practices have caused a lot of confusion over the years! � However, it's clear and indisputable that the NOJ 391 license plate moved from car to car at various times. � The NOJ 391 number plate was ultimately bolted onto and sold with the car constructed on the bent/repaired � frame from LeMans 1953. After being sold, this car had a documented club-racing history in England until� it was wrecked badly at Silverstone in 1964.� � The mystery surrounding Fred Hunter's car partly inspired Tom Kovacs to build a replica of NOJ 391. � | ||||||

�

�

Photos with file names that start "TomKovacs" are copyright Kaye Kovacs. They're used here by permission. �

No permission for subsequent republication by other parties is given or implied.�

�

Photos with file names that start "BillThumel" are copyright 2009 by Curtis Jacobson, for exclusive use by �

BritishRaceCar.com. All rights reserved.

�

| If you liked this article, you'll probably also enjoy these: | �|||||

| �

Michael Bartell '56 Healey 100M | �

| �

Joe Gunderson ~'58 MG EX186 | �

| �

Eddie Beal '78 MG MGB | �

| You're invited to discuss anything you've seen here on The British Racecar Motorsports Forum! | �|||||

�

Notice: all the articles and almost all the photos on BritishRacecar.com are by Curtis Jacobson.

�

(Photos that aren't by Curtis are explicitly credited.) Reproduction without prior written permission is prohibited.

�

Contact us to purchase images or reproduction permission. Higher resolution images are optionally available.

�

�

�

�

�