�

�

Marcus Jones drives this Lotus 18 Junior Race Car

� � Owner: Allen Fine estate� City: Mosely Virginia

� Model: 1960 Lotus 18 Junior

� Engine: 997cc Ford Anglia "Kent" engine�

�

Lotus Finds Success in Formula One

��

The Lotus 16 of 1959 had been uncompetitive in Grand Prix racing. The Coventry Climax FPF�

engine that was available to Team Lotus was very much less powerful than the Ferrari or �

BRM engines, so the Lotus strategy had been to reduce weight and to improve handling so �

they could carry more speed through turns. Simultaneously, they hoped for an aerodynamic �

advantage. Frankly, they didn't meet these goals. The Lotus 16 had excessive understeer, �

and it never placed higher than 6th in a Formula One race. �

�

The big story of 1959 was the success of a different Coventry Climax powered car: the Cooper. �

Cooper won five of nine Formula One races, plus nineteen of nineteen major Formula Two races, �

because apparently Cooper alone recognized the inherent advantages of a rear-engined �

chassis configuration. The era of front-engined Formula cars was ending.�

�

Team Lotus deserves credit for being quicker than most to see the writing on the wall.�

The brand new rear-engined Lotus 18 was ready to race in time for the beginning of the �

1960 season. Indeed, for 1960 the Lotus 18 was absolutely state of the art. Team Lotus �

accomplished all the goals Colin Chapman had set out at the beginning of the 1959 season. �

The 18 was the lightest car in the 1959 Formula One field. At the start of the Belgian �

Grand Prix, the Lotus 18 weighed-in at only 455kg whereas the closest competitor was a �

Porsche at 490kg. The total frontal area of the Lotus 18, including tires and suspension, �

was only nine square feet compared to the Cooper Climax's 9.5. Handling and coefficient �

of drag were similarly outstanding, although it's harder to quantify by what margin. �

�

Of course it doesn't hurt to have a great driver. Sterling Moss qualified fastest and �

then drove an 18 to easy victory at Monaco in May. Moss also qualified fastest for the Dutch �

Grand Prix in June, but during the race one of his wheels was damaged when a lapped car he was �

over taking kicked a kerbstone into his path. Despite stopping for repair, Moss managed to work his �

way back to fourth position. He drove the race's fastest lap in the process. Later in June, �

during practice for the Belgian Grand Prix at Spa, Moss had an accident and was injured, �

and Lotus hopes for the constructor's cup were dashed. Sterling Moss healed and returned to �

driving just in time for the end of the season. The final race was the United States Grand �

Prix at Riverside in November, where Moss once again qualified fastest and went on to race �

victory.�

�

�

"ACBC" is short for Anthony Colin Bruce Chapman, the founder of Lotus.

�

The Formula Junior Story

��

There was a lot more to Lotus than just a Formula One team. From 1959, the Lotus Group�

was comprised of three divisions. Lotus Components Limited was the division�

which built and sold racecars and racecar parts. �

�

It didn't take much work to make the Lotus 18 suitable for Formula Two. They simply �

installed a smaller Coventry Climax engine. Combined build of Formula One and Formula �

Two 18's was 24 cars. But that wasn't all! Lotus Components developed a variant of the �

design for a much lower-power racing class called Formula Junior. About 125 Lotus 18 �

Juniors were built�

�

What is a Formula Junior? Formula Junior rules defined the class as follows: �

"Cars of the Junior formula are one-seater racing cars, whereof the fundamental �

elements are derived from a touring car recognised as such by the F.I.A., �

with minimum production of 1000 units in 12 consecutive months." Maximum engine �

capacity was 1100cc, but cars powered by engines smaller than 1000cc were allowed �

a lower minimum weight of 360kg vs. 400kg (dry). "The gear box must be that of �

an F.I.A. recognized touring car. Complete freedom is left with regard to the �

number and staging of gear ratios." Few if any Formula Junior cars used �

transaxles that came from the same make or model donor car as their engines. �

Renault, Citroen, or VW transaxles were mated to Ford or BMC engines. �

The rules also stated that "The braking system and principles (viz. drum brakes �

or disc breaks) must remain the same as on the car from which is taken the engine." �

�

�

Enjoying this article? www.BritishRaceCar.com is partially funded through generous support from readers like you!

�

To contribute to our operating budget, please click here and follow the instructions.

�

(Suggested contribution is twenty bucks per year. Feel free to give more!)�

�

Except for engine, gearbox, and brakes, the Lotus 18 Junior is very similar to the �

Formula One car. The space frames of both cars integrate a sheetmetal wrapped�

mid-section bulkhead, but the Formula One chassis has a second (similar) bulkhead�

at its extreme rear. Some sources report that the Junior frame used thinner wall �

tubing. The Formula Junior version carries a single fuel tank instead of two tanks, �

it rides on narrower wheels and tires, and it's missing the Formula One car's �

adjustable rear antisway bar.�

�

For the Formula Junior, Lotus wisely chose the new Ford "Kent" four cylinder �

engine which had been introduced in 1959 and was homologated based on its use �

in the Ford Anglia saloon. The engine was peppy, partly on account of its �

oversquare 3.187"/1.906" bore to stroke ratio, its overhead valve 8-port head, �

and its lightweight, low friction, three main bearing crankshaft. Ford rated the �

stock engine at 39hp at 5000rpm and 52.5lb-ft at 2700rpm. Since the Anglia saloon �

only came with drum brakes, the Lotus 18 Junior would be obliged to utilize drum �

brakes too. Lotus chose to mate the Ford engine to a Renault 4-speed gearbox.�

�

�

Allen Fine is deceased, and his estate has decided to sell the car. Marcus Jones will be �

happy to answer any questions from interested buyers. Marcus can be reached by telephone at�

(804) 833-5482. �

�

�

�

�

�

Features and Specifications

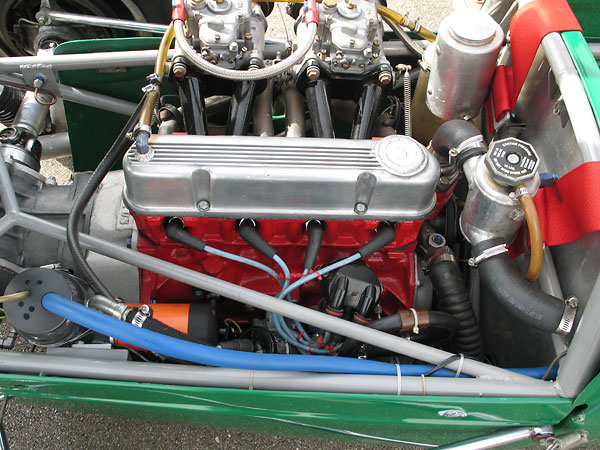

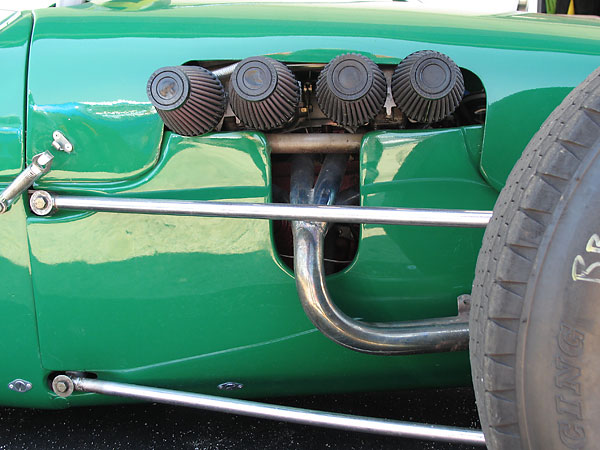

�| Engine: | �997cc Ford Anglia "Kent" engine. Non-crossflow, iron cylinder head. �

Dual Weber 40DCOE carburetors. K&N round tapered air filters (x4). �

Full race camshaft. Standard rockers. �

Lumenition Optronic optical/breakerless ignition system with �

Lumenition high performance coil, used with the Lucas 25D4 distributor.�

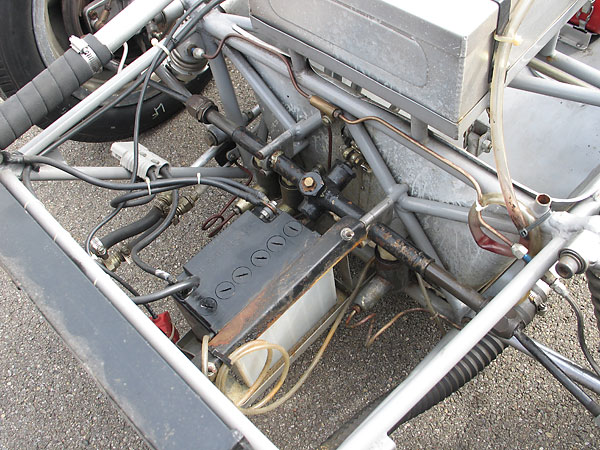

Dry sump lubrication system, including a Titan oil pump. | �

| Cooling: | �combination radiator/oil cooler. | �

| Exhaust: | �custom 4-2-1 header. | �

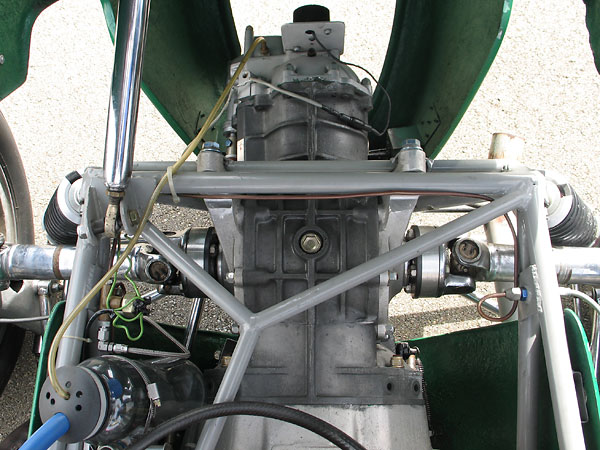

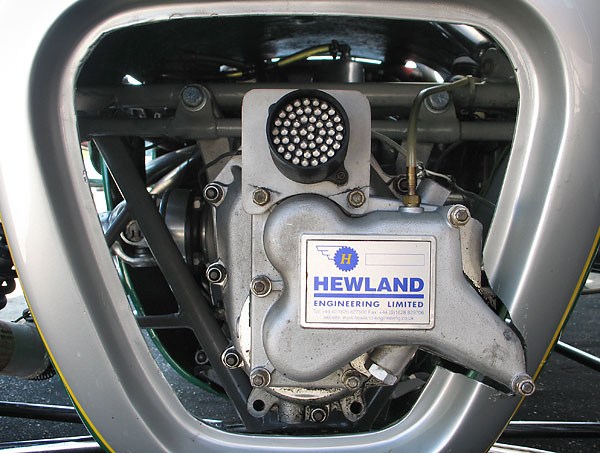

| Transaxle: | �Hewland Mk5 5-speed transaxle with open differential. (First gear is for the �

paddock only.) Tilton single disc clutch. "Lotus" adapter ring.�

(Note: adapter rings, slave cylinders, etc. are readily available from �

Taylor Race Engineering.) | �

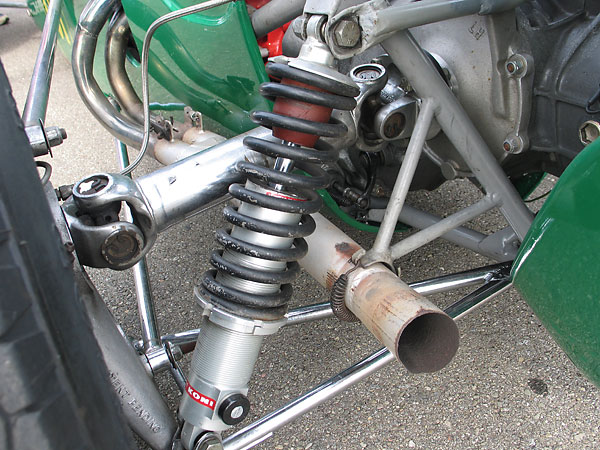

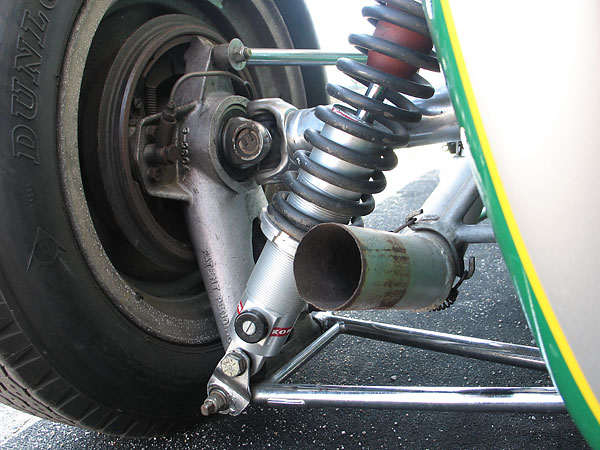

| Front Susp.: | �dual wishbone. KONI adjustable coilover shock absorbers. Anti-roll bar. | �

| Rear Susp.: | �driveshaft as upper link. Very long, reversed lower wishbones. Trailing radius rods.�

KONI adjustable coilover shock absorbers. | �

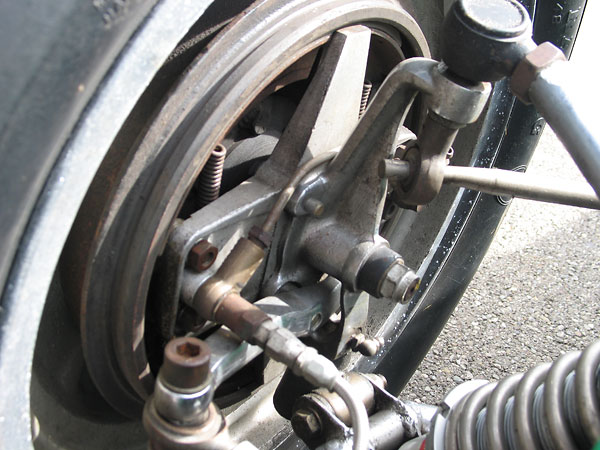

| Brakes: | �(master) dual Lockheed master cylinders with bias bar. � (front) drum. � (rear) drum. | �

| Wheels/Tires: | �Lotus "wobbly web" six-stud magnesium wheels. Dunlop Racing "204" tires, 15x4.5 front / 15x5.0 rear. | �

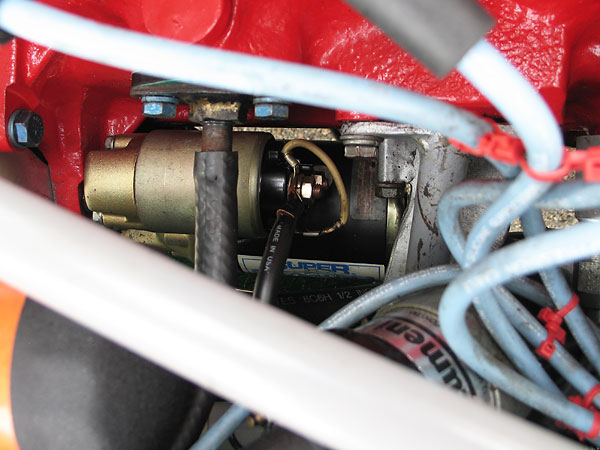

| Electrical: | �Tilton Super Starter. Wet cell motorcyle battery. | �

| Instruments: | �(left to right) Westech dual EGT gauges (700-1700F),�

Smiths coolant temperature gauge (90-230F), �

Jones mechanical tachometer (1000-9000rpm), �

Smiths oil pressure gauge (0-100psi), | �

| Fuel System: | �Fuel Safe Systems fuel cell. Facet fuel pump. | �

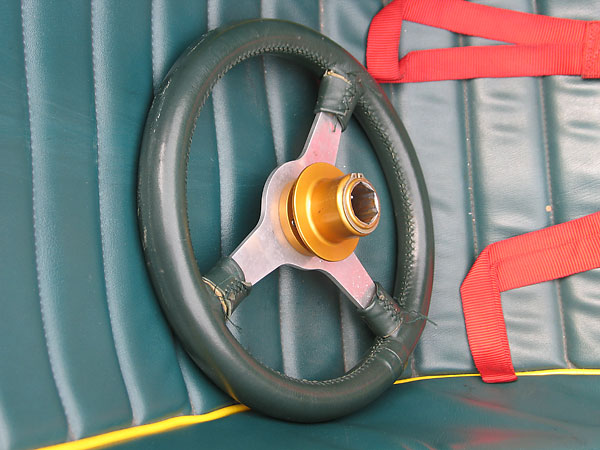

| Safety Eqpmt: | �Simpson five point cam-lock safety harness with Sabelt shoulder pads. �

Lifeline fire suppression system. �

Quick release steering wheel hub. 50 LED rain/brake light. | �

| Weight: | �885lb. | �

| Racing Class: | �Formula Junior / SVRA FJ2 | �

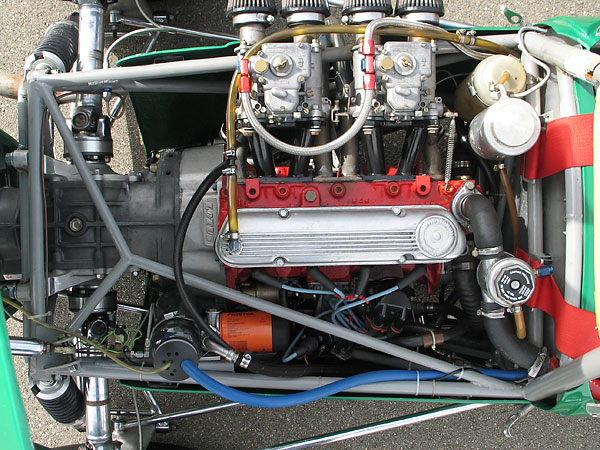

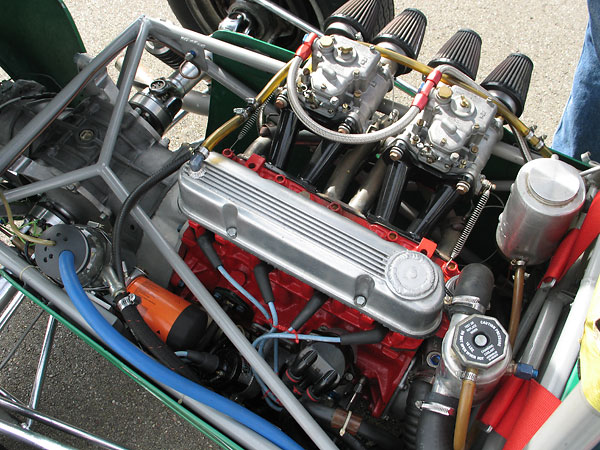

Engine Installation

��

�

997cc Ford Anglia "Kent" engine.

�

�

This engine was newly introduced in 1959 for use in Ford of Britian's Anglia (105E) saloon model.

�

�

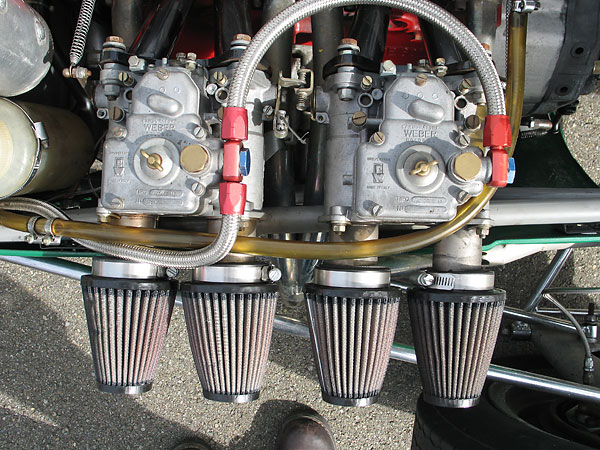

Dual Weber 40DCOE carburetors.

�

�

K&N round tapered air filters (x4).

�

�

The Webers are stamped "40DCOE18", where the 18 suffix indicates their initial set-up including jetting.

�

�

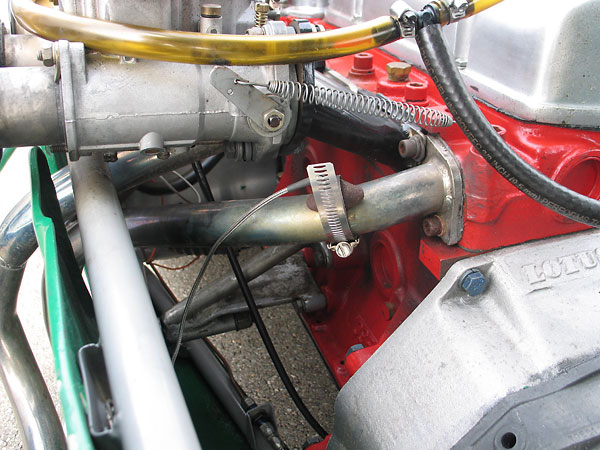

Exhaust gas temperature sensor, mounted to the exhaust header.

�

�

Four-into-Two-into-One (aka: "Tri-Y") exhaust header suits the engine's 4-2-1-3 firing order.

�

�

This is just a coolant overflow bottle and a catch tank.

�

�

Coolant header tank, with pressure cap at the high point in the system

�

�

A better view of the fabricated steel intake manifolds.

�

�

Lucas 25D4 distributor, upgraded with Lumenition "Optronic" optical pick-up breakerless ignition module.

�

�

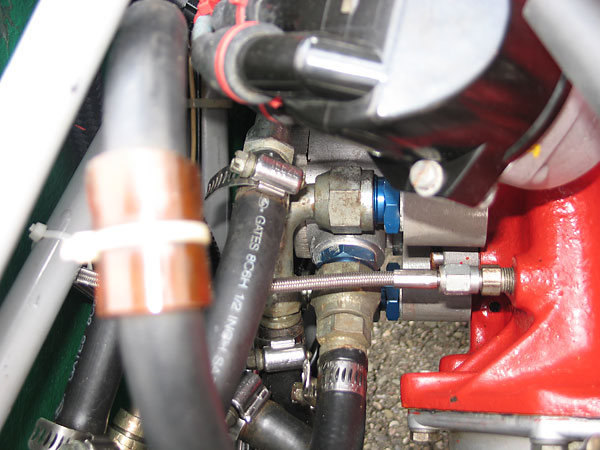

Oil pressure gauge port, and plumbing for oil cooler / remote filter.

�

�

Tilton Super Starter.

�

Transaxle

��

�

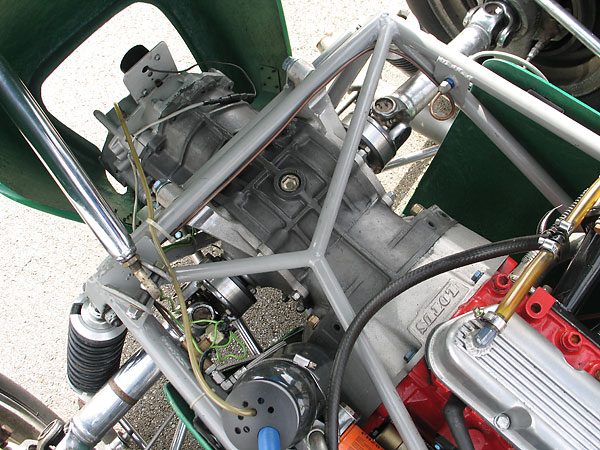

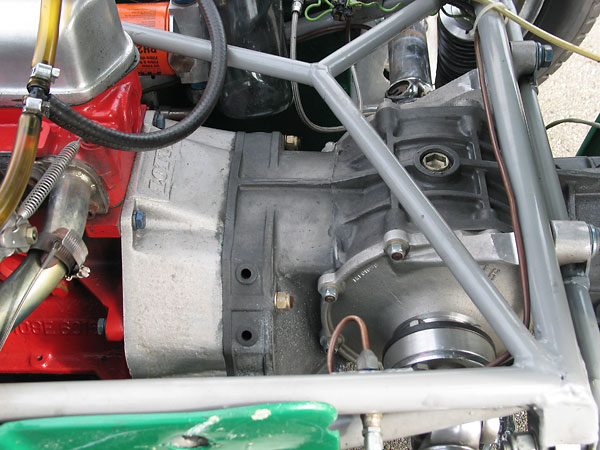

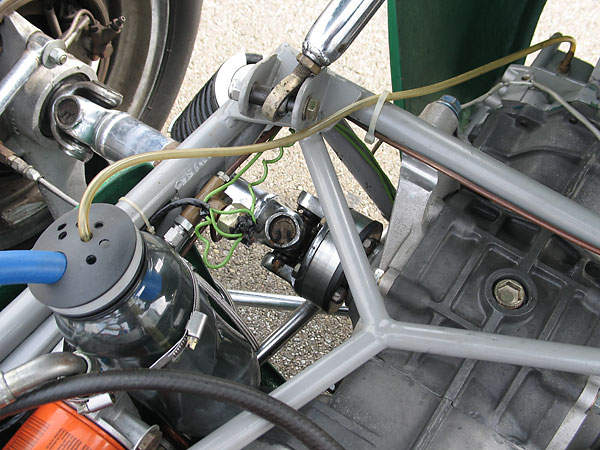

Hewland Mk5 5-speed transaxle with open differential.

�

�

Lotus 18 Juniors came with Renault Dauphine (Type 318) 4-speed gearboxes. The Hewland transaxle in this

�

car is a big upgrade. Englishman Mike Hewland started modifying Volkswagen transaxles for racing use in

�

1957. Much of Hewland's early business was for Formula Juniors, and many cars were converted. In 1961,

�

Lotus started offering Hewlands as optional equipment. Still, some vintage racing clubs forbid the upgrade.

�

�

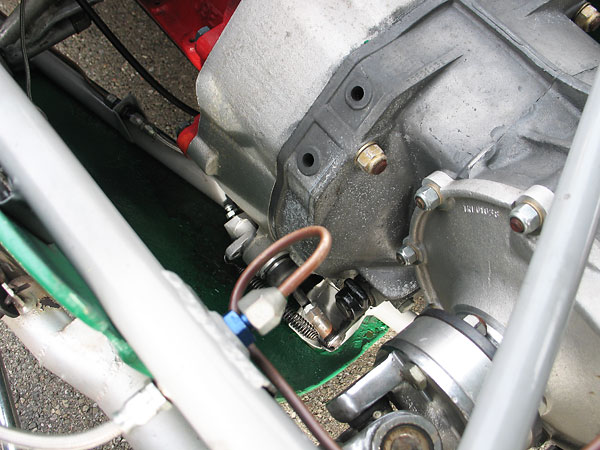

The clutch slave cylinder (7/8" bore) and transaxle adapter ring are from Taylor Race Engineering.

�

�

The transaxle appears to be a neat fit. We understand it took a lot of wiggling to get it into place.

�

�

The spherical rod end bearing (a.k.a.: "Heim joint" in U.S.A. or "Rose joint" in Great Britian) at the

�

top of this photo is part of a detachable roll hoop brace. The brace, and indeed the roll hoop itself,

�

are relatively modern concessions to safety. Lotus didn't provide any rollover protection at all. Heim

�

joints provide a convenient way to adjust the length of all sorts of radius rods. Notice that you don't

�

see a Heim joint in the very top, lefthand corner of this photo. Why not? We'll get to that!

�

�

This bright, rugged 50-LED lamp is marketed as "The Ultimate Tail/Brake Light."

�

�

Front Suspension

��

�

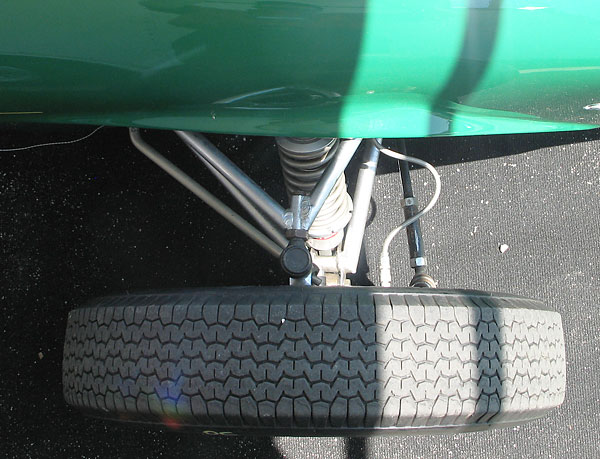

Dual wishbone front suspension.

�

�

The original Armstrong shock absorbers have been replaced with adjustable KONI shock absorbers.

�

�

To adjust caster angle, one disconnects the top wishbone and then adds or removes shims.

�

�

Steering links originally had conventional tie rod ends. Heim joints facilitate more precise adjustment.

�

�

Finned aluminum ("Alfin") brake drums are common on Formula Junior cars, but this one has iron drums.

�

The Formula One version of the Lotus 18 raced with Girling disc brakes on all four corners.

�

�

Feeding the front anti-roll bar through a Heim joint bearing is cleverly light and simple. It's a Lotus trick

�

that was also used on the Formula One Lotus 18's. Downside: roll stiffness isn't easily tuneable.

�

�

Anti-roll bar mounting bracket.

�

�

In 1958, "wobbly web" convoluted magnesium wheels became a distinctive Lotus feature. Lotus wobbly web

�

wheels proved to be both lighter and stiffer than spoke wheels. Soon, all competitive international race teams

�

switched to cast magnesium wheels. (Ferrari was last, in 1961.) Lotus wobbly web wheels were mounted on

�

studs to save weight compared to old-fashioned knock-offs. This change was facilitated by tire improvements;

�

by 1958, tire changes were no longer common during races. Why not use aluminum wheels? Magnesium

�

is about half as strong as aluminum, but it only weighs about two-thirds as much per unit of volume.

�

Rear Suspension

��

�

In 1959, Cooper started a landslide in Grand Prix development by putting their engine behind the driver.

�

Lotus was first to follow Cooper's lead, but did so with substantial technical refinements. Where Cooper

�

had used a transverse leaf spring for the rear suspension, Lotus used coilover shock absorbers. To save

�

weight and add simplicity, Lotus tried something tricky: they employed the driveshafts as de facto upper

�

suspension links instead of having separate wishbones (as in the front suspension).

�

�

Complications? The location of u-joints on the driveshafts were now suspension pivot points, so their

�

location was critically important. Also, bearings in the transaxle would have to withstand axial loads.

�

On the other hand there was no need for splined joints on the driveshafts. (Splined joints add cost and

�

can cause binding. In 1961 Lotus tried a different approach. They added upper wishbones, but made

�

fixed length shafts work by using them with donut-shaped rubber couplings to accomodate plunge.

�

�

Notice here that the upper suspension link (i.e. the halfshaft) is much shorter than the lower link. With

�

this geometry, the rear wheel will tilt toward the body (i.e. develop "negative camber") as it moves

�

upwards in bump. But when cornering, the chassis of the car will tilt outward and the net result will be

�

that the tire stays substantially perpindicular to the road surface for better grip.

�

�

Lotus designed the 18 to have both front and rear nominal suspension roll centers about and inch or so

�

above the ground. Compared to previous Grand Prix cars, weight transfer from inner to outer wheels during

�

cornering was dramatically reduced. However, this design was a bit of a compromise because the distance

�

from nominal roll center to center of gravity (i.e. the "roll couple") was increased. In simple terms, the car's

�

body would sway sideways more than other cars when turning. To mitigate this, Lotus equipped the Lotus

�

18 Grand Prix cars with both front and rear anti-sway bars. (The rear bars were adjustable.) However, Lotus

�

apparently decided against providing the Lotus 18 Juniors with rear anti-sway bars.

�

�

Lotus made these trailing links as long as feasible to help minimize rear steering effects. Notice that their

�

length isn't adjustable, so they have to be precisely made and they don't facilitate suspension tuning.

�

(Use of Heim joints on suspension radius rods was pioneered by the Cooper Car Company in 1958.)

�

�

Trailing radius rods.

�

�

KONI adjustable coilover shock absorbers.

�

�

Lower inboard suspension pivot points.

�

�

The Formula Junior races on 15"x4.50" (front) and 15"x5.00" (rear) Dunlop Racing "204" tires. However,

�

in its Formula One version the Lotus 18 raced on 15x5.00" (front) and 15x6.50" (rear) Dunlop "R5" tires.

�

�

Miscellaneous / Chassis

��

�

Fuel Safe Systems fuel cell.

�

�

Combined radiator (above) and oil cooler (below).

�

�

Wet cell motorcyle battery.

�

�

Lightweight steering rack.

�

�

The front section of the body is mounted on just a handful of Dzus quarter-turn fasteners.

�

Interior

��

�

Lotus used green gelcoat when they made the Lotus 18's fiberglass body panels.

�

�

The quick release steering wheel hub is a modern safety feature.

�

�

Smiths coolant temp gauge (90-230F), Jones tach (1000-9000rpm), Smiths oil pressure gauge (0-100psi).

�

�

�

�

LOTUS COMPONENTS

�

Cheshunt, Hertfordshire. England.

�

Chassis No. FJ719, Engine No. S182041E

�

�

�

Westech dual EGT gauge, fire suppression switch, rain light switch, fire suppression spray nozzle.

�

�

Lucas power and starter switches. Note: the original (Renault) shifter was located on the lefthand side.

�

�

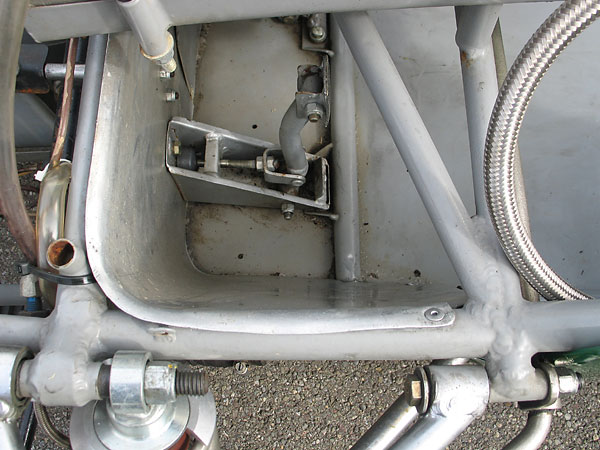

Foot box.

�

�

Lifeline fire suppression system.

�

�

Clutch pedal.

�

�

Simpson five point cam-lock safety harness with Sabelt shoulder pads.

�

�

The oil reservoir for the dry sump lubrication system is mounted behind the seat.

�

In the shadow: the Lumenition Optronic ignition module.

�

�

Facet fuel pump.

�

�

Removeable quick-release "Pip pin" comes out, and then the roll-hoop brace can be swung rearward.

�

�

Exterior

��

�

�

�

A "LeMans Style" flip-open fuel cap would have been original.

�

�

GT Classic mirror.

�

�

�

�

All photos shown here are from June 2009, when we viewed the car at The Heacock Classic Gold Cup at �

Virginia International Raceway, or from September 2009 when we viewed the car at The US Vintage Grand �

Prix at Watkins Glen. All photos by Curtis Jacobson for BritishRaceCar.com, copyright 2009. �

All rights reserved.

�

| If you liked this article, you'll probably also enjoy these: | �|||||

| �

Jay Nadelson 1957 T43 | �

| �

Jeff Snook 1956 XI LeMans | �

| �

Dick Leehr 1968 51c | �

| You're invited to discuss anything you've seen here on The British Racecar Motorsports Forum! | �|||||

�

Notice: all the articles and almost all the photos on BritishRacecar.com are by Curtis Jacobson.

�

(Photos that aren't by Curtis are explicitly credited.) Reproduction without prior written permission is prohibited.

�

Contact us to purchase images or reproduction permission. Higher resolution images are optionally available.

�

�

�