"The photos identify it, as that was the only car with the front half wings. I did those 'cause

Dittemore kept breaking them off when they were full size." - Kas Kastner (original owner)

Mead Korwin's Lola T192 Formula 5000 Racecar

Owner: Mead KorwinCity: Shelby Township, Michigan

Model: 1971 Lola T192

Engine: 305cid Chevy V8

Race prepared by: owner

Not Just a Longer Wheelbase

Lola's T192 model was developed from the previous year's Lola T190.

Many people think of the T192 as simply a lengthened version of the T190, but there are many other

important differences. This article summarizes the history of these two models and compares many

details of their designs. It also tells the story of Mead Korwin's Lola T192, which was driven by

Al Unser and Jimmy Dittemore in 1971.

The Lola T190 had been competitive from its debut race. At Sebring Florida on December 28, 1969,

Mark Donohue was handily winning before dropping out with fuel problems related to an undersize

fuel filter. Donohue praised the new T190 design, but other customers complained that they found the

T190 difficult to set up. One thing that undoubtedly slowed their climb up the learning curve was

the T190's uncommonly short wheelbase; it took some getting used to! In close contact with the Lola

works, Australian driver Frank Gardner experimented throughout the 1970 European Formula 5000 season

with lengthening and otherwise altering his T190. In August, Gardner's heavily modified T190 won at

Thruxton and at Silverstone. For the 1971 Formula 5000 season Lola would need a new model, and with

it they decided to return to a longer wheelbase.

Just nine months and one day after the T190's debut, the first Lola T192 test car

(HU192/19) was shipped to Mark Donohue at Penske Racing to drive in the final three races of

the North American Formula 5000 season. How did it do? In a rain soaked race at Mosport,

Donohue managed a remarkable feat. He won despite sliding completely off track on the very

first turn of the first lap. His left-side tires contacted a guardrail simultaneously, but

somehow his suspension was spared damage. He bounced back, literally. Donohue wasn't so lucky

at Mid-Ohio, where he spun his T192 in a practice session and tore up the floor of the

monocoque tub while sliding across apex markers. He would miss that weekend's race. It wouldn't

have been obvious to fans or competitors, but Donohue judged the prototype's handling to be

highly dysfunctional. In his memoir, he called it "darty". The prototype T192 was quickly

patched-up for a test day at Summit Point, but the repair didn't hold up. Donohue despaired

that he might miss the final race of the season.

Donohue made a phone call to Lola proprietor Eric Broadley and the two men talked it through. At

long distance, Broadley came to the conclusion that the handling problems were probably caused by

flexing of front suspension pick-up points. He very quickly provided a replacement monocoque tub

with several key improvements. The front suspension's lower pickup points were built stronger and

stiffer. Both upper and lower pick-up points were spaced further outboard. In conjunction

with shorter front A-arms, the revised mounting points provided the same front track as the

earlier prototype. According to Mark Donohue, Eric Broadley's thinking was that shorter A-arms

would provide less leverage, and thus would feed less force into the mounting points.

Donohue's T192 was rebuilt, skid-pad tested, tuned, and ready for the last race of the 1970 season.

Per the insistence of Eric Broadley, Donohue used a low-mounted rear wing at Sebring. (High-mounted

wings were already forbidden for Formula 5000 outside the U.S., and everyone knew they wouldn't

be allowed in North American Formula 5000 races starting in 1971.) Donohue later explained that

his instinct would have been to go with a high-mounted wing, but he conceded that the low-mounted

wing resulted in less drag and thus higher speed on long straight-aways. Donohue qualified fastest

and easily won the 1970 Sebring Formula 5000 race.

With the front suspension updated to suit it, the new longer wheelbase obviously worked well.

Going into the new 1971 season, the new T192 model had already won both of the two races it

had started in.

Lola T190 (left) vs. T192 (right): an elaborate fabricated arch is replaced by a far simpler flat panel.

For the record, the Lola T192 featured in this article measures 99 inches from front hub center

to rear hub center. That measurement compares to 88 inches for the Lola T190 model.¹

A close look at the T192 reveals many improvements besides wheelbase that made it simpler,

more robust, and more easily serviceable than its predecessor. The T190 and T192

monocoque tubs themselves are quite different. Contrary to common assumption, Lola didn't

just "stretch" the T190's aluminum monocoque tub to achieve a longer wheelbase. In fact, they

redesigned every part of the fabrication from the shifter lever forward. Generally, the

T192 design is comprised of fewer and less elaborate parts.

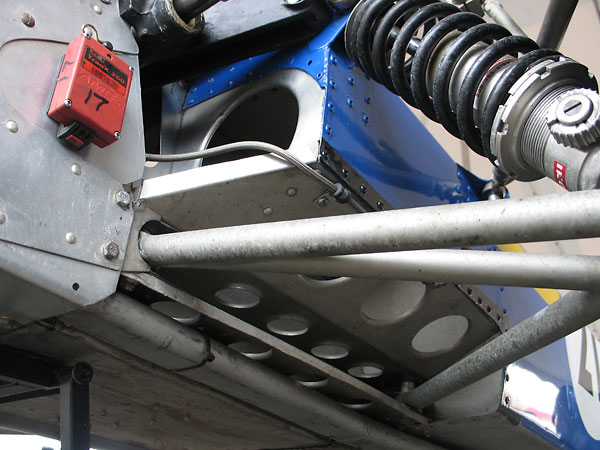

Roll hoop braces spanned rearward across the engine, and connected to a new magnesium crossmember.

The T192 featured a whole different rollover structure, which was developed after Sebring to comply

with new SCCA roll-bar requirements. Donohue's T192 was updated over the winter, and all subsequent

T192's were equipped with a two inch taller roll-bar with new bolted-on braces over the engine.

One might assume that with these braces the chassis may have been marginally stiffer for a small

improvement in handling. However when we asked Bob Marston, Lola's Chief Engineer through most of

the Formula 5000 era, he explained: "To my recollection we didn't have any chassis stiffness issues

and hence were not looking for improvements in that area." The purpose of the braces was only to

meet or exceed rule requirements.

At the back, the roll hoop braces attached to a rear crossmember that spanned across and helped

support the transaxle. Where the T190 had an elaborate fabricated steel crossmember assembly,

the new T192 utilized a custom casting of lightweight magnesium. Bob Marston continued: "The change

from the T190 steel fabrication was prompted by the need for weight savings but more importantly a

casting is much more efficient in function and economical to produce compared to a fabrication, once

the initial patterns have been made."

The bodywork was quite different too. The T190 came with a one-piece fiberglass body that

extended from nose to roll-hoop. For even the most minor service - like refueling the car - the

whole panel had to come off. (On the T190, fuel caps were mounted under the bodywork, and no filler

lids were provided.) The T192 came with a two piece body. Its nosecone could be removed quickly to access

the radiator. Its rear body section had hinged fuel filler lids. Access to the master cylinders

was very much improved too. To get at the T190's master cylinders, the radiator and all its ductwork

have to be removed first. Because of this inconvenience, the master cylinders are equipped with

remotely mounted reservoirs. On the T192, access to the master cylinders is provided by simply

loosening four Dzus quarter-turn fasteners and removing an access panel. Master cylinders with

integral reservoirs further reduce complexity.

Although bodywork changes made the T192 somewhat more serviceable, their primary benefit was

a lower profile nose section with a smaller opening for the cooling system, which helped

reduce aerodynamic drag.

Kas Kastner and John Brophy shortly after receiving Lola chassis number HU192/22, sans engine!

(Note also that the T192 originally came with Firestone tires, but Kastner-Brophy Racing switched

to Goodyear tires because Goodyear was willing to sponsor all four of the team's racecars.)

A Tough First Race

Lola's build records show that chassis number HU192/22 (with Hewland DG300 transaxle number 211)

was originally shipped on February 17, 1971 to their North American distributor Carl Haas,

along with invoice number was "1035". The car was then delivered to Kastner-Brophy Racing

at their brand new shop.

Kastner-Brophy Racing was a partnership of R.W. "Kas" Kastner and John Brophy. Kas Kastner

was already famous among sports car enthusiasts for running Triumph's North American racing

program through the sixties, and for writing the classic performance manuals for Triumph

sports cars.² Since 1951, Kastner had been close friends with John Brophy, a Salt Lake

City disc jockey turned Los Angeles advertising executive. With Kastner's encouragement,

Brophy had already become active in sports car racing at the club level. The two put together

a business plan, as described in the Triumph Sports Owners Association's February 1971

newsletter: "Kastner-Brophy will act as competition consultants to British Leyland and will

carry on development programs for the firm as part of their racing assignment. Located at

429 East Alondra Blvd., Gardena, Calif., they are in the business of building complete

race cars of any type. The firm has full facilities for fabricating bodies, paint

work, engine dynamometer testing and suspension development." In this capacity, Kas Kastner

signed for three new Triumph sports cars, plus a Lola the partners would race for fun.

Then the phone rang. Carl Haas called to request loan of Kastner-Brophy's brand new

Lola T192 to reigning Indianapolis 500 and 1970 USAC Champion Al Unser for use in the Questor

Grand Prix of Sunday March 28, 1971. The Questor Grand Prix was an exhibition race that would

pit Formula One cars against Formula 5000 cars on a brand new high speed racetrack built east

of Los Angeles in Ontario, California that combined banked oval sections and a "road" section

through the infield.

After introductions were made, Unser's chief mechanic George Bignotti handled the arrangements.

Bignotti was the most successful team manager in Indy 500 and USAC history, and he managed a

team of ten full-time professionals plus a network of suppliers. He agreed to take the car

as a rolling chassis, prepare it for the Questor race, and return it with a Traco Engineering

built Chevy V8 engine. The engine was paid for by "Besteel", a Los Angeles area steel

distributor, so the car would wear their logo. For the Questor race, the Kastner-Brophy Lola T192

was assigned number 33 (which would be changed to 11 for the Formula 5000 season) and it would

wear its number on a white paint job.

How did the Questor race go? Unfortunately, many of the American drivers including both

Al Unser and Mark Donohue were obliged to miss practice due to a conflict with USAC's

Phoenix 150 race on Saturday. Unser won the Phoenix race, but he qualified poorly for the

Questor Grand Prix. He qualified 26th fastest, which meant he would start 13 rows behind a

pace car driven by actor James Garner. The race consisted of two 100 mile heats, but Unser

retired just halfway through the first heat (on lap 17 of 32) and he didn't start the second

heat. Unser told the press that his engine had lost oil pressure, but in fact that was a

gracious little fib. The engine was fine, but the car became almost undriveable due to

defective (sagging) suspension springs.

The Southern California crowd was rooting for American-engined cars and American drivers.

It particularly cheered for Mark Donohue, who put on a wonderful show. Donohue qualified seventh,

battled his way up to third place, and maintained that position until the beginning of the last

lap of heat one. Then his engine started sputtering and he crossed the finish line in ninth

place. Thus, he would start the second heat from ninth position. Since Donohue believed his

car had simply run out of gas, he started heat two with a heavier fuel load. In just five laps,

Donohue moved up through the Formula One cars into third position, but the fuel supply problem

came back and he was forced to throw in the towel. After the race it was discovered that a

partially clogged breather vent had caused the problems. Nonetheless, Donohue's performance

proved that a small block Chevy powered Lola T192 Formula 5000 car could run with the best

Formula One cars on a fast circuit despite a huge difference in engine cost.³

Kastner-Brophy Racing's Lola T192: Chassis HU192/22

After the Questor Grand Prix, Lola HU192/22 returned to the Kastner-Brophy shop, where the

team had less than one month to prepare for the first race of the 1971 L&M Formula 5000

championship season. Kastner had already recruited Max Kelley to be chief mechanic. Kelley's

background was both broad and deep, having worked for John Mecom and for the Shelby American

organization through their respective glory days. Kelley was Crew Chief at LeMans on the

victorious 1966 Ford GT-40 team. He was also Crew Chief on James Garner's Cherokee Racing

team in 1969, where he prepared a Surtees TS5 for Formula 5000. Kastner recruited Jim

Dittemore to drive the Kastner-Brophy Lola. Although all of Dittemore's racing experience

was in relatively low power sports cars, Kas Kastner had developed a great friendship and

respect for Dittemore when they'd worked together campaigning Triumphs in SCCA national races.

Jimmy Dittemore proved to be a quick study, and equally importantly the team worked well

together.

Al Unser had quietly warned the team about handling problems, so the first order of business

was to strap Dittemore into the driver's seat and try the car out. Although Dittemore wasn't

entirely sure what a Formula 5000 car should feel like, he didn't have to complete a whole lap

to decide this one was nearly undriveable. "I don't know how Unser drove it as far as he did!"

Nonetheless, the team tore into the problem and got quickly to the bottom of it. Kelley's

approach was to make changes and send Dittemore back out. He repeatedly told Dittemore: "It

will be better, worse, or about the same. Just tell me which one." The main problem was soon

found to be defective suspension springs. Kastner remembers that the rear springs had sagged.

Dittemore remembers it was the fronts. Either way, all four springs were replaced and the whole

suspension was realigned. Next the team experimented with various anti-sway bars, some of

which Kastner fabricated himself. They learned their way around the car, and quickly grew

to appreciate its potential.

Dittemore credits Kastner as a super tuner with a real affinity for reading spark plugs

and for getting the most out of fuel injection. Back in earlier days, Kastner and Dittemore

had raced a Triumph TR250 which included Triumph's European-spec fuel injection system

instead of side-draught carburetors. Even as their Chevy motors grew tired, Dittemore figures

that Kastner kept the engines as precisely tuned-up as they could've been.

Kastner remembers it a little differently: "Jimmy was very good in the car, but our engine

supply was mostly poor." The first engine, from Traco Engineering, only ever produced 450bhp.

That simply wasn't enough. Dittemore knew it from the first race on April 25th at Riverside,

where he lost ground on every long straightaway. On the other hand, the T192's brakes seemed

to be a big advantage; he felt he could brake harder than competitors and trust that his

brakes wouldn't fade. Dittemore particularly leveraged this advantage over Sam Posey, who

had to change his line and braking points dramatically in the later stage of races.

Dittemore might not be able to keep up on straights, but he could show up and fill Posey's

mirrors in the turns. Through intimidation, he found he could get Posey to make mistakes.

Jimmy Dittemore earned a second place trophy at Riverside, and Sam Posey settled for third.

Jim Dittemore, Kas Kastner and John Brophy at Riverside for the first race of 1971.

Kastner decided to dig into his pocket and buy an Al Bartz engine. The one he bought

was dyno tested at 505bhp. That's obviously stronger, but it still wasn't as much power as

richer competitors would have. With only barely enough money for two race engines to last

a whole season, Kastner-Brophy Racing had to be conservative. They initially planned to swap

engines back and forth, using the Bartz engine for qualifying and the Traco engine for races,

but that strategy didn't pan out. The team just did the best they could as the season wore on.

Kastner: "The new Bartz engine broke a valve head the first time we ran it at Kent,

Washington so we went back to the old engine again. The repaired Bartz made the balance of

the year. Al Bartz did not charge me for the valve, but for everything else."

The eight race 1971 North American Formula 5000 season was dominated by two teams. David Hobbs

drove his McLaren M10B to qualify fastest five times and to win five races. Sam Posey drove

his Surtees TS8 to qualify fastest three times and to win two races. Dittemore believes that

a big part of their success, especially in qualifying, was that their two teams arrived at each

venue about two days ahead of most of the field. In those days, arriving early meant they

had extra days to practice and to tune their cars with subtle but important chassis changes

like anti-sway bar and wing angle adjustments. Of course more practice for the drivers didn't

hurt either.

The fourth round of the Formula 5000 season was held at Mid-Ohio. It was a track Jim Dittemore

had never driven before, and he knew having to learn the track would be a big disadvantage,

but his accident in heat one had nothing to do with inexperience. The team had modified the car's

throttle pedal with a lip on the righthand edge to help position the driver's foot. Somehow the

lip bent over and jammed against the right-hand wall of the footbox, and the car powered right

off the edge of the track. A pair of front suspension wishbones was destroyed, but the tub wasn't

badly damaged. The throttle pedal - still stuck when the car towed into the paddock - was replaced.

Luckily, the engine was "okay" and two weeks later the car was ready for round five.

At Road America, Jimmy Dittemore showed his skill and resiliency. On that famously fast

road course, Dittemore qualified fourth and finished fourth in the first heat, 31 seconds

behind Jerry Hansen's winning Lola T192. (David Hobbs finished second, 4 seconds back.

Canadian Eppie Wietzes finished third, on Hobbs' tail. Sam Posey finished fifth, seventeen

seconds behind Dittemore.) Jimmy improved and was leading the second heat outright until

lap 18 of 24 when his engine finally gave out. He was forced to retire by a blown head

gasket.

Al Bartz had seen the performance, and he came over to visit Kastner-Brophy in the paddock

with an offer: "I think I can find forty or fifty more horsepower for you." Unfortunately,

the team didn't have money or time to take Bartz up on it. They would have to find success

on their own terms and on a shoestring budget. They rebounded from setback at Road America

to a third place finish two weeks later at Edmonton in "The Lucerne 100".

Readers like you are keeping BritishRaceCar.com online and growing through voluntary financial contributions.

If you like what you've found so far, and you want to see more, please click here and follow the instructions.

(Suggested contribution is twenty bucks per year. Feel free to give more!)

Just one weekend after The Lucerne 100, the "The Seafair 200" at Kent Washington was one of

the focal points of Seattle's great annual festival. Although it attracted top Formula 5000

competitors, it wasn't part of the Championship Series - it was a USAC sanctioned exhibition race.

USAC had a reputation for very strict rules and enforcement in the pits, but Kastner and

Dittemore found the USAC officials particularly accommodating. As Kastner tells the story:

"There were three sessions of qualifying. We were in the first session. Car in the pit lane.

Would not fire up. Worked all through that session. Second session and the chief tech guy

came by to see what was going on. He was very sympathetic and did not force us to leave

the pit lane. Most unusual! That would have stopped us totally. The second session was complete,

but still no spark. The last session starts and then in the middle of that session, Max Kelley

found a wire that had been crushed on the engine change, fixed the wiring, and Jimmy went out

with four minutes remaining." If he'd had the whole session, he might well have used it.

However, only his best lap would count towards determining starting order in the race's

first heat. As it turned out, Dittemore only circled the track twice before someone blew-up

their engine and oiled the track, ending the session a little early. The better of Dittemore's

two laps was clocked at 1:20.33, which put him in the thirteenth spot. (Sam Posey and David Hobbs had

qualified quickest at 1:16.45 and 1:16.56, respectively.)

From his worst starting position of the season, Jim Dittemore fought his way through the

crowded field and capitalized on the mistakes of others. Sam Posey retired early from the

first heat with an oil leak, and later David Hobbs retired too. Dittemore pulled into

the lead and held on to win. In the second heat, Posey would come back and edge Dittemore

into second place, but on averaged results Jim Dittemore was easily the race winner. The

rookie team was elated. They had shown tenacity, beat a very credible field, had won $7400

in prize money, and had done it all in a "plain wrapper" (essentially unsponsored and plain

white colored) race car. Since Seafair was the only road race on USAC's 1971 calendar,

Jim Dittemore will always be remembered by some as "USAC's 1971 Road Racing Champion".

From Kent, it was 1600 miles East to Brainerd for The Minnesota Grand Prix on the very

next weekend. There, another blown head gasket caused overheating and an anti-climatic

retirement: "it was just an old, old engine. It was too expensive to go back for the final race."

At the end of our interview, Kas summarized their memorable year of Formula 5000 racing neatly:

"I must say Jimmy was just outstanding in the car and we did pretty well for a bunch of

pick-me-ups with no money to spend."

Jim Dittemore's results with HU192/22 in 1971

| Venue | Date | Qualified | Finished | Notes | |

| 1 | Riverside | April 25 | 9 | 2 | (Heat 1: 3rd, Heat 2: 4th) |

| 2 | Laguna Seca | May 2 | 9 | 4 | (Heat 1: 6th, Heat 2: 4th) |

| 3 | Seattle | May 23 | 9 | 9 | (Heat 1: 5th, Heat 2: DNF/engine) |

| 4 | Mid-Ohio | July 5 | 10 | DNF | (Heat 1: DNF/accident, Heat 2: DNS) |

| 5 | Road America | July 18 | 4 | 9 | (Heat 1: 4th, Heat 2: DNF/engine) |

| 6 | Edmonton | August 1 | 6 | 3 | (Heat 1: 3rd, Heat 2: 4th) |

| N/A | Seattle | August 7 | 13 | 1 | (Heat 1: 1st, Heat 2: 2nd) |

| 7 | Brainerd | August 15 | 6 | 24 | (Heat 1: DNF/overheating, Heat 2: 15th) |

| 8 | Lime Rock | September 6 | X | X | (Didn't participate.) |

Jim Dittemore at round three of the L&M Grand Prix - Continental 5000 Championship series.

Seattle International Raceway - May 22-23, 1971 - Kent, Washington

Features and Specifications

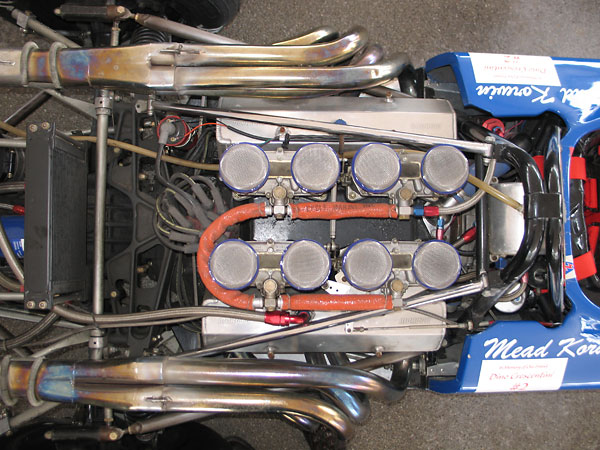

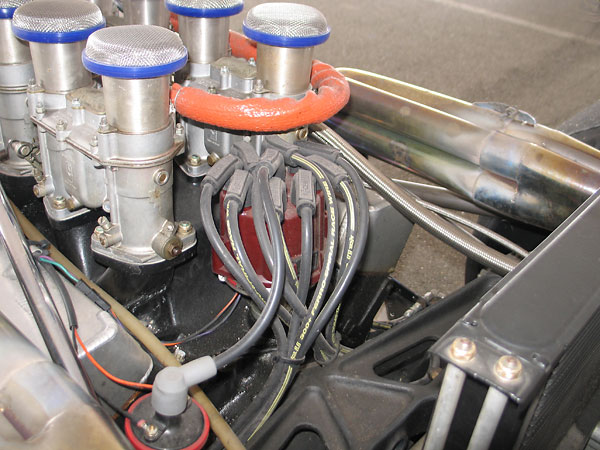

| Engine: | four Weber 48IDA carburetors on an Inglese intake manifold.

MSD distributor.

MSD Blaster 2 ignition coil.

Accel 8.8 300+ Ferro-Spiral Race Wire ignition leads.

Moroso aluminum valve covers. |

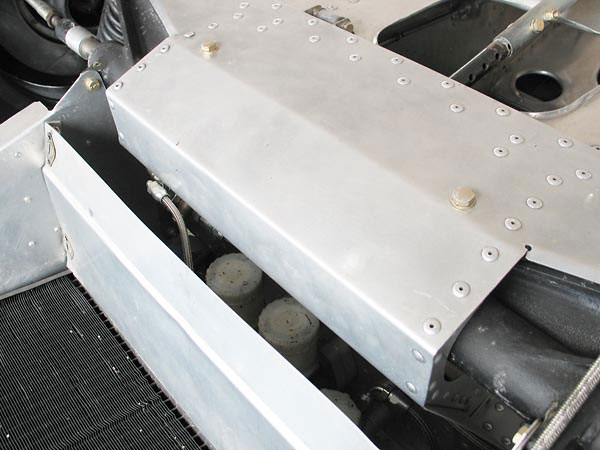

| Cooling: | Serck brass dual-pass radiator. |

| Exhaust: | four into one headers. |

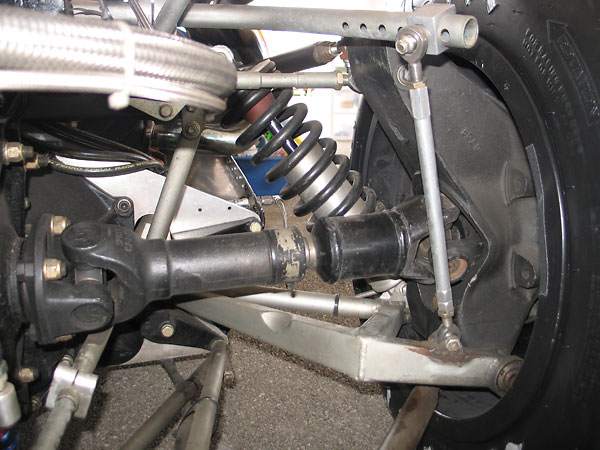

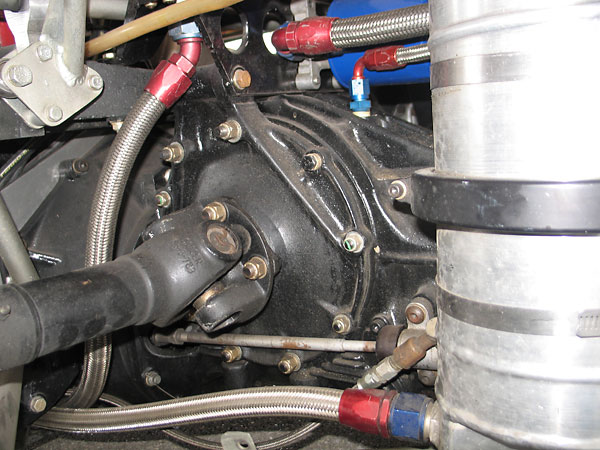

| Transaxle: | Hewland DG300 five speed.

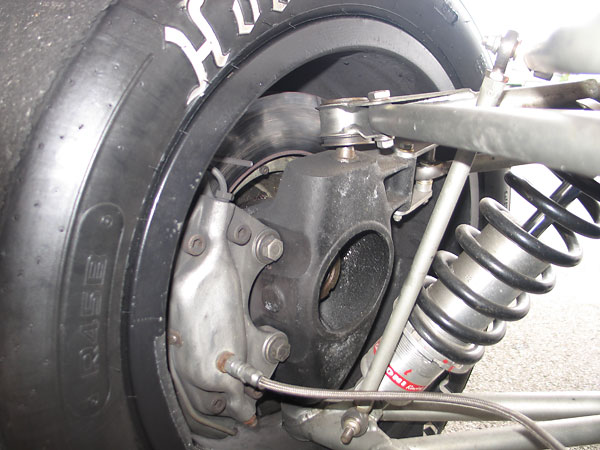

The halfshafts feature spline-joints in lieu of the original Metalastic donuts. |

| Front Susp.: | KONI 8212 coilover shock absorbers.

Adjustable anti-sway bar. |

| Rear Susp.: | KONI 8212 coilover shock absorbers.

Adjustable anti-sway bar. |

| Brakes: | (master) dual Lockheed master cylinders with bias bar. (front) Girling calipers and 12" vented and slotted rotors. (rear) Girling calipers and 12" vented and slotted rotors. |

| Wheels/Tires: | Lola wheels. Hoosier R45B compound tires (24.0/11.0/15 front, 27.0/15.0/15 rear). |

| Electrical: | Lucas battery disconnect switch. |

| Instruments: | (left to right)

AutoMeter ProComp Ultra-Lite fuel pressure gauge (0-15psi),

AutoMeter Carbon Fiber Ultra-Lite water temperature gauge (100-250F),

AutoMeter Carbon Fiber Ultra-Lite tachometer (0-10000rpm)

AutoMeter Carbon Fiber Ultra-Lite oil pressure gauge (0-100psi). |

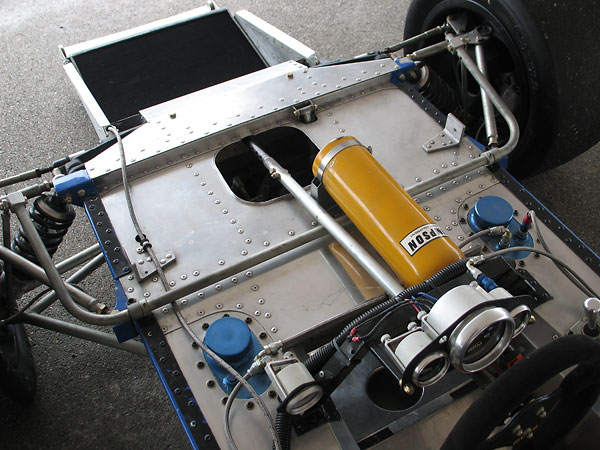

| Fuel System: | Peterson billet aluminum fuel filter. |

| Safety Eqpmt: | OMP six point camlock safety harness.

Strange Engineering quick release steering wheel hub, on a Momo steering wheel.

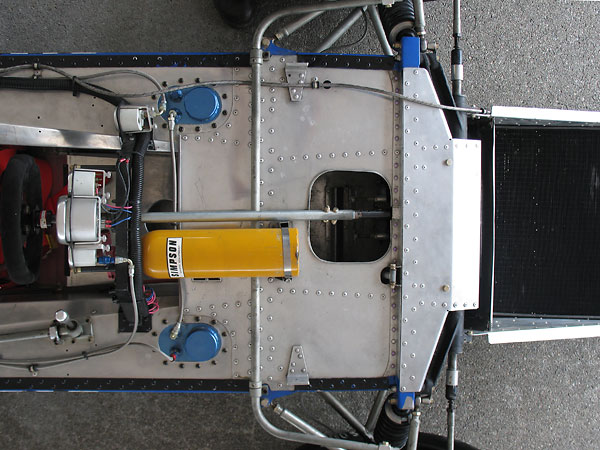

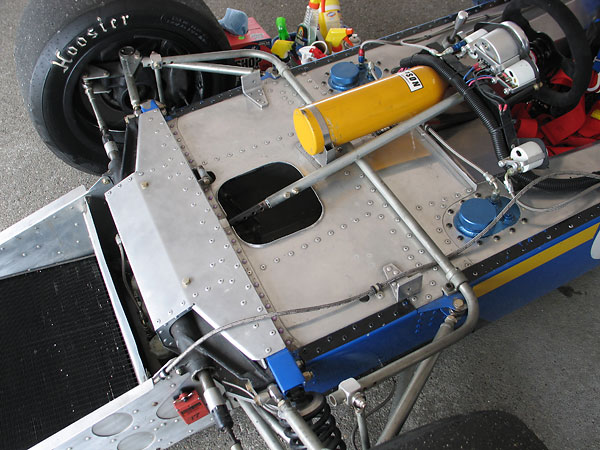

Vintage Simpson centralized fire suppression system. |

| Weight: | (1350# was the minimum allowed weight for 1971.) |

| Racing Class: | Formula 5000 |

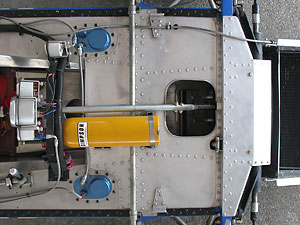

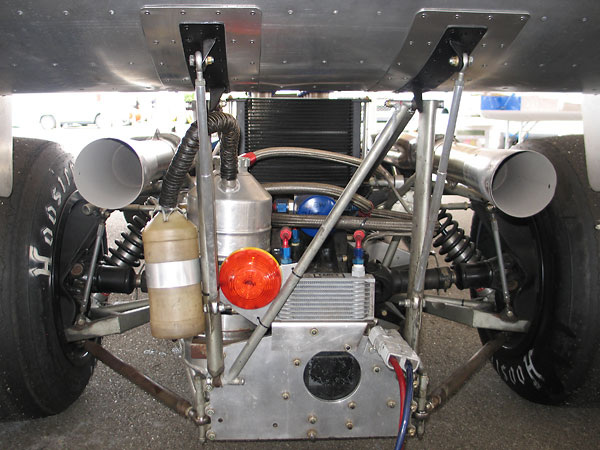

Engine Installation

Mead currently runs four Weber 48IDA carburetors, but throughout 1971 his car was always fuel injected.

(The carbs are mounted on an earlier model Inglese manifold, similar to Inglese's current NG1919 model.)

MSD distributor and Blaster 2 ignition coil. Accel 8.8 300+ Ferro-Spiral Race Wire ignition leads.

Free flowing four-into-one headers.

Coolant header tank and Lucas battery disconnect switch. Since there's no

charging system, disconnecting the battery will stop the engine.

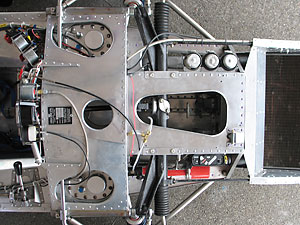

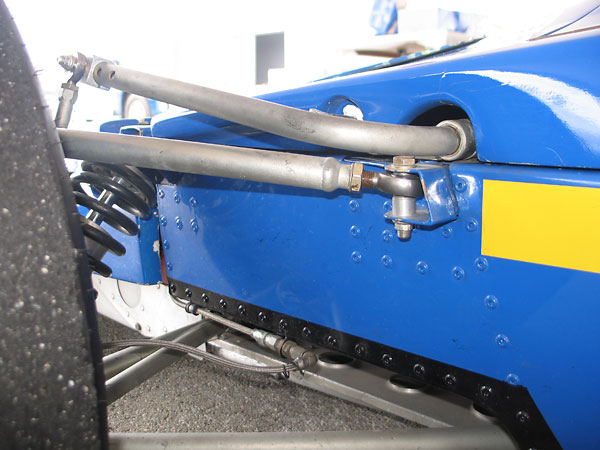

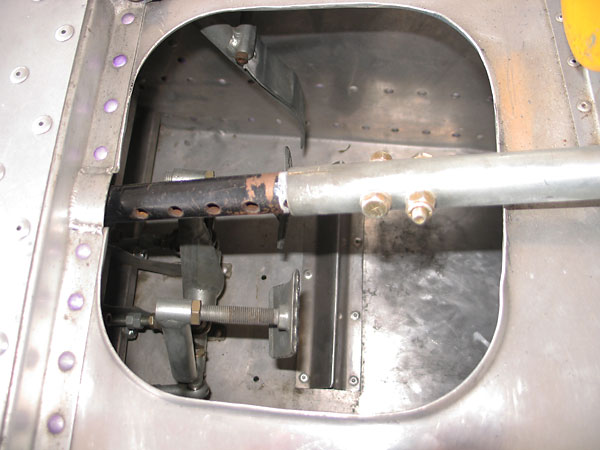

Front Suspension / Steering / Etc.

T192 front lower control arms are braced rearward, rather than forward like usual Lola practice.

Lola developed a steering rack and pinion assembly expressly for the T190. It featured an elaborate but

lightweight cast magnesium housing. For some mysterious reason the pinion was offset 1.07" to the left.

This component was carried over to the T192 model, but special brackets were added (as shown here)

when Eric Broadley decided to relocate upper wishbone mounting points two inches further outboard,

Lola also changed the upper control arm rearward fixings from horizontal to vertical bolts.

This orientation gave Lola customers a little more latitude to experiment with anti-dive.

Punched holes reduce weight. Bellmouth profiled flares around the holes add stiffness. Lola's T190

featured custom-contoured flared lightening holes for specific locations on the tub. Round flared

lightening holes, as shown here, are generally easier and quicker to produce with off-the-shelf tools.

Aluminum coolant piping is routed below the lower-front suspension pickups (and also the fuel tanks).

Apparently beefier: Lola T192 lower control arms are made from three tubes instead of two.

Magnesium uprights and Girling disc brakes carry over from T190.

Enjoying this article? www.BritishRaceCar.com is partially funded through generous support from readers like you!

To contribute to our operating budget, please click here and follow the instructions.

(Suggested contribution is twenty bucks per year. Feel free to give more!)

This view shows a high proportion of "blind" or "pulled" rivets. These may date to the relatively minor

accident at Mid-Ohio in 1971. Since no one seems to recall the full extent of those repairs, we asked

Bob Marston how many of these rivets might be original: "Lola policy for all chassis that were intended

for the more powerful and heavier formulae [was that] solid rivets would always be used wherever possible.

Obviously there were some internal areas that you couldn't get to with the block to flatten the tail of

the rivet, so a blind or pulled rivet as you would call it was used. Where there are now a lot of pulled

rivets installed on the cars, I would suspect they are there as a result of some earlier repair work."

We don't know what anti-sway bars were originally installed on the T192, but we know it was raced

at about the time tubular anti-sway bars were replacing solid ones in professional racing. Seamless

4130 chrome moly steel was typically used. The trick was heat treatment. Without proper heat

treatment, the bars would have yielded in use and given unpredictable results.

Lockheed master cylinders with integral reservoirs are accessible by removing the panel at left.

(The Lola T190 featured Girling master cylinders with remote-mounted reservoirs.)

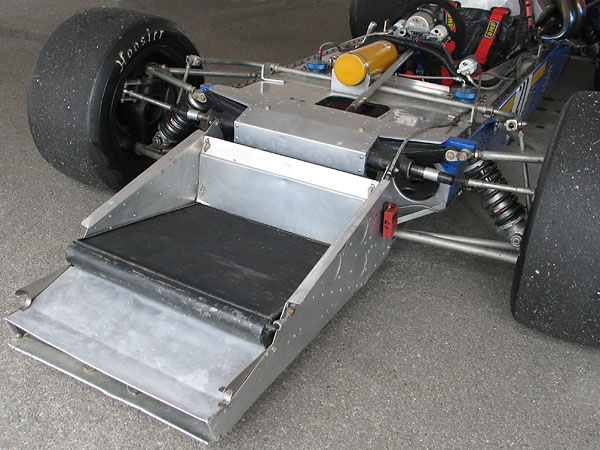

The Lola T192 features significantly lower-profile ductwork and nose cone bodywork than the T190 model,

but the Serck dual pass radiator and its mounting are otherwise essentially similar.

This Simpson fire extinguisher is unchanged since it was installed in 1971; thankfully it's still unused after

all these years. Simpson Safety Equipment started producing parachutes for dragsters in 1959, and

introduced their first flameproof driver's suits in 1964. It's been years since they made fire extinguishers.

On the Lola T192, instruments are mounted to a simple structure of steel box tubing. Note also that the

car's chassis plate is attached underneath the fire extinguisher, so we didn't get a close-up photo of it.

We did verify that it's stamped HU192/22. The "22" is clearly shown in the hi-res version of this photo, as

is the newer Lola Cars Ltd. company address (from January 1971): "Huntingdon" instead of "Slough".4

Rear Suspension / Transaxle / Etc.

Hewland DG300 five speed. Earl's brand transaxle oil cooler.

Lola proprietary magnesium rear upright.

A splined-coupling midway between Spicer universal joints takes up "plunge" as the suspension works.

According to Lola documentation, both the T190 and the T192 models originally came with Metalastic

rubber donuts for this purpose. Rubber donuts were preferred over splined joints because they avoided

any "stiction" or binding which might negatively affect the car's handling. However, Metalastic donuts

have become an expensive maintenance item in the large (5.25") size that's required for Formula 5000.

Girling clutch slave cylinder. (It doesn't get used much during races since the Hewland is a dog ring box.)

Interior

AutoMeter ProComp Ultra-Lite fuel pressure gauge, AutoMeter Carbon Fiber Ultra-Lite

water temperature gauge, tachometer, and oil pressure gauges.

All vintage racecars must carry a functional fire extinguisher of some description.

This vintage Simpson fire suppression kit is about as simple as built-in systems get.

This nifty little three-switch panel isn't original to the Lola design. The gear selector

(at right) is yet another detail that was changed between T190 and T192 designs.

OMP six point camlock safety harness.

Quick release steering wheel hubs are valuable safety equipment. They help corner workers extract drivers

after accidents. This Strange Engineering hub is installed on a Momo ergonomic steering wheel. The first

documented use of quick release hubs we're aware of was on McLaren M23 Formula One cars, circa 1973.

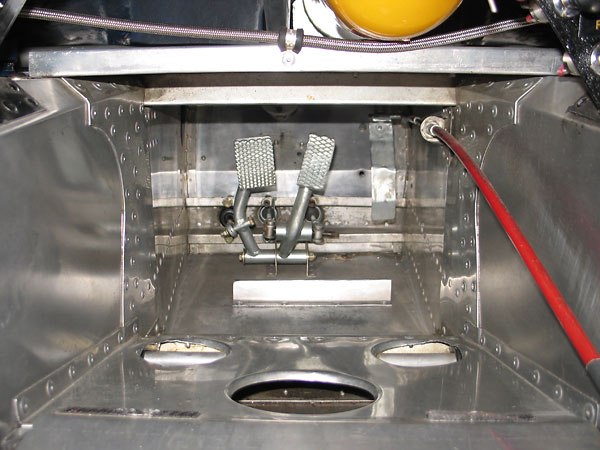

The steering column can be adjusted forward and back. The driver's heels are supported by a heel bar

and the pedals can be adjusted so their motion matches the natural arc of the balls of the driver's feet.

More footroom. Whereas the T190 footbox tapers inward continuously as it goes forward, the T192 footbox

tapers outward from 11.5" wide at the driver's shins to about 14" wide at the front bulkhead. There seems

to be just enough extra room for a left-foot footrest ("dead pedal"), although one hasn't been installed yet.

The T192 brake pedal bracket is simply unflanged, thin-gauge aluminum and it's riveted to the floorboard.

Unlike the T190 version, the sides of the bracket aren't tied together and the pedal's footprint is smaller.

One is left to wonder if a more robust brake pedal bracket wouldn't improve pedal feel at the limit.

Exterior

We enjoyed watching Mead race his Lola T192 at the 2009 U.S. Vintage Grand Prix of Watkins Glen,

where his best lap of the weekend was a very impressively fast 2:01.043, for an average of 101.1mph

over the challenging 3.4 mile circuit. Mead was third quickest in an excellent Formula 5000 field. After

one race, stewards checked Mead's engine and found it to be well within displacement limits.

Mead gets a lucky handshake from a member of Team Bedford Racing. Since they don't have

their own car yet, Team Bedford generously pitches in and helps any racer that can use a hand.

With its chisel-profile nose and long, low stance the Lola T192 looks fast even when it's sitting still.

One of the most interesting experimental modifications Kastner-Brophy Racing made to their Lola T192

was installation of small custom wings on either side of the main roll hoop. (They're not shown here,

but we understand they were attached at the height of the rearward braces.) Kastner-Brophy tested

this novel concept at some length, but never utilized it in a race. Their conclusion? The small wings

created downforce, but probably caused a net loss due to reduced performance of the main rear wing.

The Lola T192 featured hinged fuel lids, whereas refueling a T190 required removal of the fiberglass body.

The T192 body is comprised of two seperate panels. Pushbutton operated quick-release "pip pins"

(shown at left) secure the rear panel. The front panel is held fast with Dzus quarter-turn fasteners.

"In Memory of Our Friend Dino Crescentini"

Dino Crescentini (1947-2008) was an enthusiastic, skilled, and successful vintage racer who died

in a racing accident at Mosport. As a member of the 1994 San Marino Winter Olympic Team,

Dino competed at Lillehammer in the two man bobsleigh event.

Front: Lola wheels with Hoosier Road Racing 24.0/11.0/15 Tires, R45B compound.

Rear: Lola wheels with Hoosier Road Racing 27.0/15.0/15 Tires, R45B compound.

| Notes: | |||||||

| (1) |

Over the years, quite a few different wheelbase measurements have been published for the

Lola T190 and T192 models respectively. When writing about

Eric Haga's Lola T190 in a previous BritishRaceCar.com

article, we reprinted some of the original sales literature provided by Charlie Hayes Racing

Equipment (a sub-distributor under Carl Haas). Those documents cited a wheelbase of 92".

However, in the course of researching Mead Korwin's Lola T192 we asked former Lola Chief

Engineer Bob Marston about the increase in wheelbase. Bob visited with Glyn Jones, head of

the Lola Heritage division of Lola Cars International, and reported back as follows:

When we checked the original T190 layouts, the wheelbase was definitely 88" and not any of the many other dimensions that I have seen quoted. Regarding the T192 wheelbase, the specific T192 layout drawings cannot be located along with the relevant spec sheets so unfortunately we have no way of verifying the "factory" dimension. I can only suggest you contact any T192 owners that you know and request they do an actual measurement for you. (Then use the most common number!) | ||||||

| (2) |

Later in his career, Kas Kastner would manage Can-Am and Indy Car teams, and ultimately

become Motorsports National Manager for Nissan of North America (from 1986-1990) through

the period when Nissan dominated IMSA GTP racing. He continued his career at Nissan as

Vice President of Nissan Performance Technology Inc. Kastner has written several tremendously

valuable books about building, repairing, and racing Triumph sports cars, and about Triumph

racing history. Three of these books are currently available for purchase at

www.kaskastner.com, and a fourth is currently

being completed.

| ||||||

| (3) |

As you might expect, the mainstream media ignored Donohue's performance and instead repeated

pre-programmed talking points: "production-based American engines simply couldn't compete with

Formula One technology". This dubious conclusion pretty much killed any chance of a rematch at

Ontario the following year. Both heats of the Questor Grand Prix were won by American driver

Mario Andretti in a Ferrari, with second place going to Scottish driver Jackie Stewart

in a Tyrrell-Ford. However, before dropping out Donohue's Lola was running ahead of Denny Hulme

(third, in a McLaren-Ford), Chris Amon (fourth, in a Matra-Simca), and Jo Siffert (fifth, in a

BRM.)

| ||||||

| (4) |

Between production of their T190 and T192 models, Lola Cars Ltd. moved about 85 miles north from

Slough (on the western edge of London) to Huntingdon (northwest of Cambridge). One might assume

that such a move would be very disruptive to production. We asked Bob Marston about it, and learned

that the transition actually went remarkably smoothly and quickly. Before the move, Lola was a

company of some sixty or seventy employees working in a rented facility. Bob recalls that Lola

lost no more than about ten employees to the move.

The move between Slough and Huntingdon was carried out in January of 1971 and undertaken, in the main, by our own employees. Only the heaviest of the machinery was entrusted to an outside transportation company. Such was the enthusiasm of our workforce that the move was completed in a few days even though the approach area to the new factory was incomplete and most of the surrounding area was a mud bath (this being January of course with all the attendant problems of a UK winter)! From the company perspective the move was ideal. Land and premises could be purchased (at preferential rates, I believe) instead of rented, besides which this region already hosted like-minded companies such as Specialised Mouldings (for GRP bodywork) and Arch Motors (for Tubular Chassis), both also located in Huntingdon, plus reasonably close proximity of Cosworth Engineering in Northampton, a mere 40 minutes drive away. Combine this with being reasonably equispaced from most of the major circuits and the move can be seen to make a lot of sense both from the commercial and practical viewpoint. Lola Cars Ltd. remains located in the same facility at Huntingdon to this day. | ||||||

The three black-and-white photos shown above are from Kas Kastner's personal archive and

are used here with his express and exclusive written permission.

All color photos shown here are from September 2009 when we viewed the car at The US Vintage Grand

Prix at Watkins Glen. All color photos by Curtis Jacobson and Don Moyer for BritishRaceCar.com,

copyright 2010. All rights reserved.

| If you liked this article, you'll probably also enjoy these: | |||||

|

Tom Grudovich '60 Lola Mk.1 |

|

Eric Haga '70 Lola T190 |

|

Seb Coppola '71 Lola T192 |

| You're invited to discuss anything you've seen here on The British Racecar Motorsports Forum! | |||||

Notice: all the articles and almost all the photos on BritishRacecar.com are by Curtis Jacobson.

(Photos that aren't by Curtis are explicitly credited.) Reproduction without prior written permission is prohibited.

Contact us to purchase images or reproduction permission. Higher resolution images are optionally available.